Laparoscopic Equipment #

While we await the results of prospective trials to determine the benefits of specific procedures, one thing is certain- laparoscopic surgery is here to stay, and surgeons of the 21st century must possess basic laparoscopic skills.

Videoendoscopic surgery, or the use of fibreoptic scopes, cameras and video monitors to perform surgery in an existing or potential anatomic space, has permeated most of the surgical sub-specialities. Neurosurgeons perform endoscopic surgery within the ventricles. Plastic surgeons perform endoscopic carpal tunnel release in the wrist and also do some facial cosmetic procedures endoscopically. Some surgeons are using the endoscopic approach in the neck for thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Vascular, cardiovascular and thoracic surgeons are also using endoscopic techniques to approach lungs, aortic aneurysms, peripheral vessel and coronary artery bypass grafts.This chapter focuses on basic equipment and techniques used in endoscopic surgery of the peritoneal cavity, ie. laparoscopic surgery.

Laparoscopic Equipment #

Quality, functional equipment is vital to the performance of a successful and efficient laparoscopic operation. The surgeon must be familiar with the equipment and must be able to troubleshoot equipment problems. In fact, the operating room nurses and all surgical personnel should be familiar with the equipment, and the formation of a specialized “Laparoscopic Team” is likely the most efficient solution.

Laparoscopes #

The standard laparoscope in general surgery is 10 mm in diameter, whereas gynecologists often use slightly smaller 7 mm scopes. The angle of the lens may be 0 degree (looking end-on) or angled at 30 degrees or greater. Most surgeons find the 30 degree scope provides an excellent view for basic laparoscopic procedures. Recently, smaller “mini-laparoscopes” of 1.5 to 3.5 mm in diameter have been introduced, which may be of either fibre optic or rod-lens construction.

Video #

Today, the term `laparoscopy’ implies `videolaparoscopy’, or the attachment of a video camera to the lighted telescope into the abdomen. Initially, laparoscopy was performed with the surgeon looking directly into the eyepiece of the scope, held inside the patient’s abdomen. Now virtually all laparoscopy is videolaparoscopy where the image is displayed on a video monitor. Hence there is surgical hand-eye separation which contributes to the technical difficulty of laparoscopic surgery.

It is often advantageous to have two monitors, one on each side of the operating table. The specific position of video monitors depends on the operation. In general the monitors are located on the pathology side, and the surgeon stands across the table, facing the video. The video cassette recorder, video monitor, light source and gas insufflator are usually housed in a single tower (Figure 7.1).

Light Source and Gas Insufflator #

Light Source

Early laparoscopes used an incandescent light bulb at the tip of the scope. The development of fiber optics has led to the movement of the light source and its controls to a separate and distant unit connected to the endoscope with a light cord (Figure 7.2a)

Gas Insufflator #

Gas insufflation of the peritoneal cavity converts the potential space into an actual one, several litres in size. Gas flow is continuous with an adjustable rate (up to 6 – 10 L/min) and maximum pressure control (maximum 12-15 mmHg recommended).

Carbon dioxide is the most commonly used insufflation gas since it is rapidly absorbed into the circulation, thus minimizing the potential for gas embolism. Nitrous oxide has been used under local anesthesia since it is purported to be less irritating to the peritoneum. The disadvantage of nitrous oxide is that it supports combustion, preventing the use of cautery, and thus limiting its usefulness as an insufflation gas.

Special laparoscopic retractors of the anterior abdominal wall (“abdominal wall lifters”) permit creation of a potential space without continuous gas insufflation, theoretically decreasing the potential for gas embolism. Abdominal wall lifters have been advocated when large blood vessels such as hepatic veins are being transected, but there is no good evidence to support their use.

Laparoscopic Instruments #

Laprascopic Instruments

Many laparoscopic instruments are modifications of standard surgical instruments. The tips are finer and are mounted on long (30 cm) shafts to pass through the abdominal wall to the operative site. Other laparoscopic instruments are unique in that they do not have counterparts in open surgery (e.g. L-hook and spatula cautery instruments). Instruments which rely on sharp surfaces may be either reusable or disposable. Disposable instruments have the advantage of staying sharper but the disadvantage of higher cost.

a) Veress Needle. A needle for obtaining closed access to the peritoneal cavity in order to create a pneumoperitoneum. It has a spring-loaded obturator which retracts to expose the sharp tip while there is resistance passing through the abdominal wall, and advances over the needle tip upon entering the peritoneal cavity (Figure 7.2b).

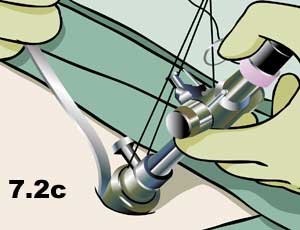

b) Hasson Cannula. A device for establishing open access to the peritoneal cavity. This consists of a 10 cm blunt trocar and 11 mm cannula which can be fastened to the abdominal wall to prevent gas leakage or cannula slippage (Figure 7.2c).

c) Trocars and Cannulas. Fundamental tools of laparoscopic surgery which provide and maintain access to the peritoneal cavity for the insertion of operating instruments. A cannula is a hollow tube of various diameters (3-20 mm, commonly 5 or 11 mm). This is placed through the abdominal wall with a sharp inner trocar which is then removed. Trocars are either metal (reusable) , plastic (disposable), or a hybrid of the two with a reusable cannula and a plastic trocar (Figure 7.3).

d) Scissors. Scissors are used for sharp or blunt dissection, with or without electrocautery. Varieties include straight, curved and hook scissors. Hook scissors are designed so that the tips come together prior to the cutting surface so that a tubular structure can be grasped and then held away from surrounding tissue for safe cutting (Figure 7.4).

e) Graspers. Numerous different types of graspers are available for grasping tissue or specimens such as gallstones. These can be traumatic or atraumatic (with or without teeth), and with or without a ratcheted handle that keeps the jaws closed without manual pressure (Figure 7.5). The tripod grasper is useful for grasping a thick-walled gallbladder (Figure 7.6).

f) Dissectors. Multiple different types with similar designs to open instruments. Fine straight dissector, Maryland and Mixter are shown here. (Figure 7.7)

g ) Cautery Tips. A variety of shapes of cautery tips are available for monopolar electrocautery dissection. The most common varieties are the L-hook and spatula (Figure 7.8).

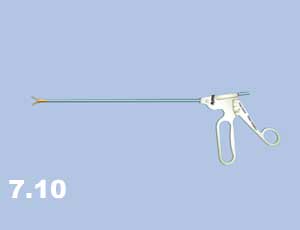

h) Needle Drivers. Laparoscopic needle drivers are similar to standard needle drivers (Figure 7.9). As opposed to most instruments which have pistol-grip handles, needle drivers usually have co-axial handles to facilitate “palming” the instrument (Figure 7.10).

i) Endoloop. Pre-tied ligature used for controlling blind-ended structures such as the appendix. An endoloop may also be placed over the end of a structure previously clipped and cut where the clip may be inadequate alone (i.e. large cystic duct) (Figure 7.11).

j) Suction and irrigation device. Important instrument for keeping the operative field clean and dry (blood is magnified on the screen, and the dark colour not only absorbs the light but directly obscures anatomy) (Figure 7.12).

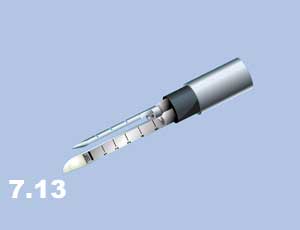

k) Endoscopic stapler. Similar uses as in open surgery, but requires a 12 mm cannula (Figure 7.13). This fires two double rows of staples and cuts between them.

Operating Table Set-Up #

Operating Table Set-Up

Sterile drape the patient widely to maximize flexibility of port site positions. Port sites represent a finite number of views of the operative field. Choose them wisely but do not feel restricted in adding extra ports as needed. However, extra ports actually add little extra morbidity. Several animal and clinical studies have concluded that the physiologic stress of one long incision appears to be greater than that of several short incisions of the same total incision length.

Plan position of patient, surgeon, assistant, scrub nurse, and videolaparoscopic equipment, and organize the “cables” accordingly. A suction and irrigation device should be immediately available for any laparoscopic case i.e. setup, and turned on.