Description #

This unit is intended for training of undergraduate, clerkship, and the first year of the core residency program in order to learn the practical aspects and techniques for holding and handling surgical instruments.

Learning Objectives #

At the end of this unit, students should be able:

1) Operating the Scalpel

2) Operating Scissors

3) Operating a Needle Holder

4) Operating Tissue Forceps

5) Operating Clamps

Overview #

The use of surgical instruments for specific tasks may require skills that positively affect the outcome of a surgical procedure.

These skills include holding, handling, and maneuvering surgical instruments in such a way that makes the performance of the surgical procedure safer, easier, smoother, and faster.

It is important to mention that there are no specific rules and regulations for the holding and handling of surgical instruments.

Individual surgeons may develop their own style of operating. Therefore, it is feasible to select specific maneuvers from different operators and form a style that one is most comfortable with.

The specific aim of this chapter is to introduce the most commonly used (classic) methods for holding, handling and maneuvering surgical instruments during operating procedures.

Contents #

Operating the Scalpel

Handling a Scalpel

Holding a Scalpel

Incision Techniques

Operating Scissors

Holding Scissors

Using Scissors

Operating a Needle Holder

Holding Needle Holders

Loading a Needle Holder

Operating Tissue Forceps

Holding Tissue Forceps

Using Tissue Forceps

Operating Clamps

Holding a Surgical Clamp

Using a Surgical Clamp

Operating the Scalpel #

Handling a Scalpel

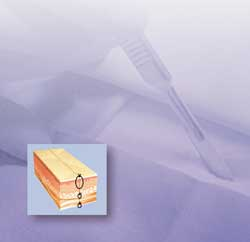

A scalpel is a sharp instrument and therefore it is important to use extreme caution when handling. In terms of handling sharp objects in the operating room, treat every patient as though they have a blood-borne transmissible disease.

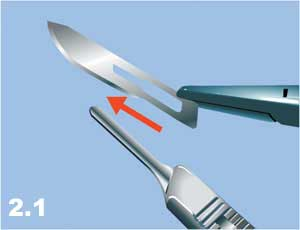

a) Loading. Loading and unloading of the blade must be done with a hemostatic clamp or needle driver by grasping the body of the blade and sliding the blade onto the hub of the handle (Figure 2.1).

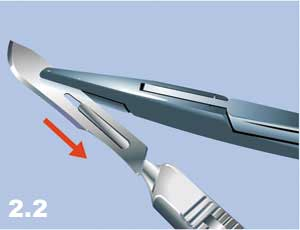

b) Unloading. To unload the scalpel, grasp the proximal end of the blade with a hemostatic clamp, push the blade slightly upward to unlock the body of the blade, and separate the blade from the handle by sliding the blade upward (Figure 2.2).

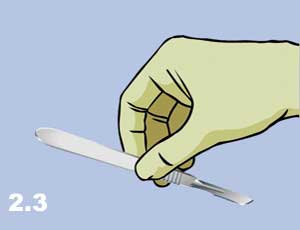

c) Giving. To give the scalpel to another person, the scalpel should be grasped with the sharp edge of the blade downward, the head toward the person who is giving the scalpel and the handle toward the person who is receiving the scalpel (Figure 2.3).

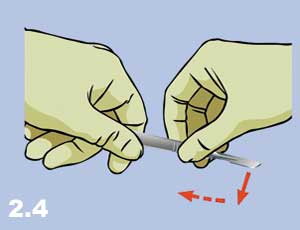

d) Receiving. To receive the scalpel, grasp the handle and move the scalpel down and then toward yourself (Figure 2.4).

NB: A scalpel is a sharp instrument, hence: The scalpel must not be loaded and unloaded manually – use instruments. The scalpel must never be passed to others with the sharp end toward the receiver as it may injure the receiving individual. When receiving the scalpel, do not pull the scalpel as it may cut the fingers of the other person.

Holding a Scalpel

The most important principle to remember when holding a scalpel is to have full control of the instrument and at the same time, to have freedom of movement. There are three common ways to hold a scalpel:

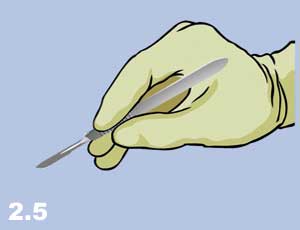

a) The Pencil Grip (Figure 2.5). This grip is used to perform small, precise incisions often with a #15 blade. With this grip, the cutting direction can be changed 360° by moving the hand and wrist (with little upper arm movement).

b) The Fingertip Grip (Figure 2.6). This grip is used to make long, straight, or curved incisions. This technique provides a great deal of maneuverability due to the flexibility of the arm, wrist, and fingers. As a result, it is frequently used in surgery.

c) The Palm Grip (Figure 2.7). This is the strongest grip and used when a precise movement with a great deal of pressure is required. The hand and wrist are kept relatively fixed, and the scalpel is held parallel with the skin to maximize the cutting edge of the blade. This grip has very limited maneuverability.

Incision Techniques #

General Principles:

The most important principles for the use of the scalpel are as follows:

a) planning and measuring before cutting.

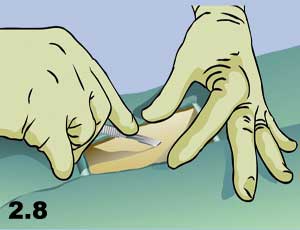

b) stabilizing the skin during an incision (Figure 2.8).

c) placing the knife perpendicular to the tissue plane and cutting straight and clean (Figure 2.9).

d) cutting the tissue layer by layer.

e) focusing your attention on the direction of the scalpel when cutting.

Methods:

The most common methods of incision with a scalpel are:

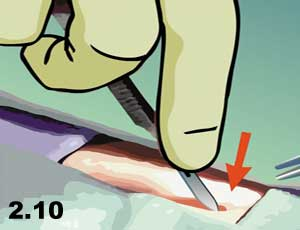

a) Press Cutting (Figure 2.10). The scalpel is pressed into the depth of the tissue with a straight movement, like stabbing.

b) Slide Cutting (Figure 2.11). The sharp edge of the blade slides on the surface of the tissue with a specific pressure and depth.

c) Sawing (Figure 2.12). The cutting is performed by sliding the sharp edge of the blade with push-pull movements, like sawing a log.

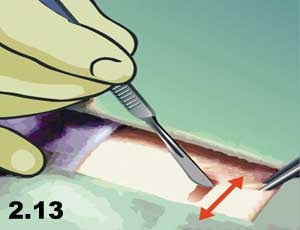

d) Scraping (Figure 2.13). The scalpel blade is held at an acute angle to the tissue surface to be scraped and used with a side-sliding motion on the surface of the tissue, similar to shaving whiskers with a straight razor blade.

Operating Scissors #

Holding Scissors

The most common ways to hold scissors are as follows:

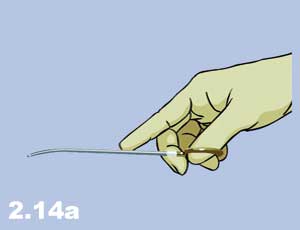

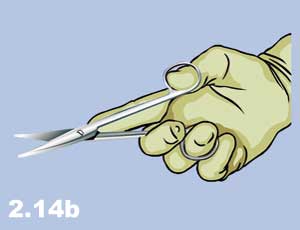

a) Thumb-Ring Finger Grip. The thumb and ring fingers are inserted into the scissor rings, the middle finger is rested in front and on top of the ring finger, and the index finger is placed on the shanks (Figure 2.14a and 2.14b). This is the most common grip for precise cutting of the tissue and for maximum control.

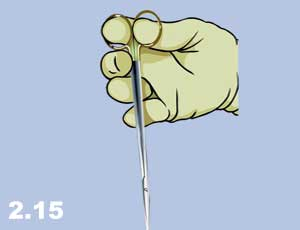

b) Thumb-Index Finger Grip. In this grip, the thumb and the index finger are placed into the rings and the body of the scissors is placed in the palm of the hand (Figure 2.15). This grip is used for direction control in reverse cutting or for deep body cavities such as the chest.

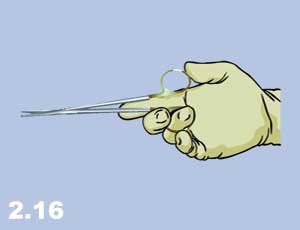

c) One Finger Grip. The scissors are held by one finger in one ring (Figure 2.16) and no finger in the other ring. This method does not provide a good grip and is rarely used.

d) No Finger Grip. The scissors are held with no fingers in the rings (Figure 2.17) This grip is primarily for using right-handed scissors with the left hand and has very limited use.

Using Scissors

General Principles:

The most important principles for using scissors are:

a) Use the most comfortable grip that provides the best stability for direction control.

b) Do not push the fingers far into the ring. Use only the tips of the fingers to operate the scissors and use the tips of the scissors for cutting.

c) Control hemostasis before cutting.

d) Always measure and think before cutting.

e) When cutting sutures, secure a good position in order to see both the suture to be divided and the tips of the scissors. This will prevent cutting other structures.

f) When bringing scissors into the surgical field or approaching a suture to be cut, keep the tips closed, open and cut, then retrieve. Do not “dive-bomb” into the field with the jaws wide open.

g) Ensure that the suture is cut before withdrawing the scissors otherwise traction may be put on an incompletely cut suture which may disrupt the vessel being ligated.

h) Squeeze the blades of the scissors together so that the sharp edges “grind” together as they cut (especially for thick sutures such as “0” or larger).

Movement:

Three types of movements can be made with scissors: closing, torque, and shearing. With these three forces, it is possible to chew-cut, crush-cut, or push-cut the tissue. Scissors can also be used for blunt dissection.

Operating a Needle Holder #

Holding Needle Holders

Four types of grips are commonly used for needle holders:

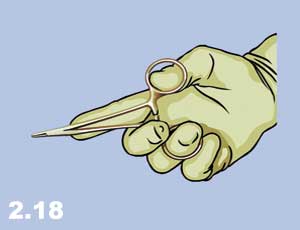

a) Thumb-Ring-Finger Grip (Figure 2.18) is the same as described for scissors.

b) Palm Grip (Figure 2.19) is the strongest grip used in places where it is difficult to advance the needle.

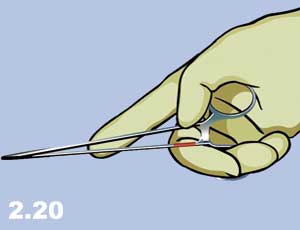

c) Ring-Finger Grip (Figure 2.20) is when the needle holder is in the palm of the hand with only the ring finger in one of the rings.

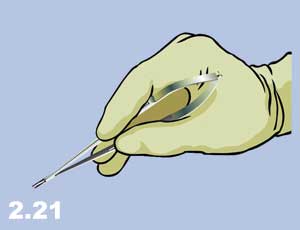

d) Pencil Grip (Figure 2.21) is used with Castrovajo type needle holders

Loading a Needle Holder with a Needle #

The relationship of the needle and the needle holder jaw is important to mention in this chapter due to frequent problems, such as bending the needle, which can happen when the needle is held by the needle holder too far back near the tail. Excessive torque on the needle, instead of driving the needle with pronation and supination of the wrist, results in the bending and breaking of the needle.

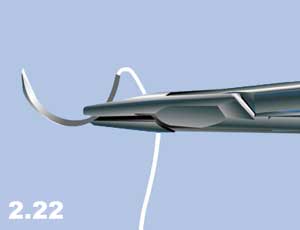

In special circumstances, the needle holder can be placed close to the point at the front of the needle, in the middle of the needle body or close to the tail of the needle, as required. However, one of the most commonly used methods is to visually divide the needle into three parts and place the jaw of the needle holder onto the border between the middle third and the tail of the needle (Figure 2.22) This position leaves sufficient length for the needle to pass through the thickness of the tissue while preventing it from bending and deformation. The tail of the needle is the weakest part of the needle.

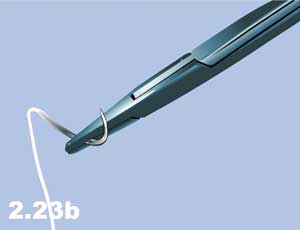

Needles can be placed with different angles in relation to the needle holder, i.e. perpendicular to the holder (right angle, Figure 2.22) or at a wide (Figure 2.23a) or sharp (Figure 2.23b) angle “hooking the needle”.

NB: The angle of the needle with respect to the needle holder should be chosen in such a way to make the needle perpendicular to the line of sewing. In other words, the angle of the needle should be related to the position of the operator.

General Principles #

The most important principles in operating a needle holder are:

a) Avoidance of Stuttering. Stuttering describes the non-productive repetition of steps that needed to be done only once. This occurs most often before the needle is in the tissue.

b) Avoidance of Stammering. Stammering is described as an interruption during a step that could be done with one motion and usually occurs after the needle is inserted into the tissue.

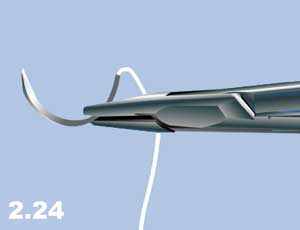

c) A forehand stitch should be started from the far side of the wound and sewn toward oneself (Figure 2.24).

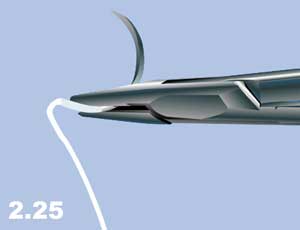

d) A backhand stitch starts from the near side and finishes at the far side; the needle is loaded backward (Figure 2.25).

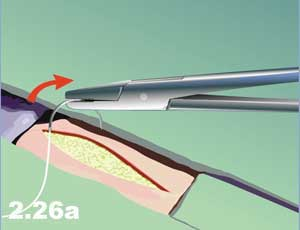

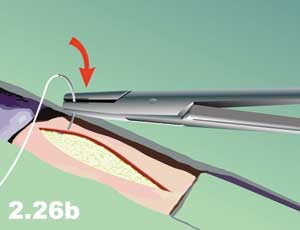

e) The needle should be placed perpendicular to the tissue plane. The driving force is always in the direction of the segment of a needle within the tissue. The rotating force must be non-stressful and done with the rotation of the wrist. (Figure 2.26a and b).

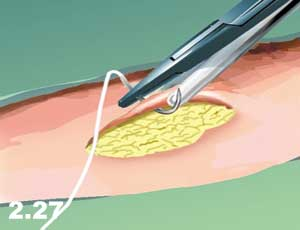

f) The far side of the wound should be grasped gently by forceps and everted outward to expose both the under layers and the needle entrance in the wound (Figure 2.27).

g) On the near side of the wound, the target layer is grasped by the forceps and the needle pushed through. In order to see the needle exit, grasp the upper layers and retract them away from oneself.

h) When sewing is complete, keep the sharp end of the needle backward and parallel to the needle holder (Figure 2.28).

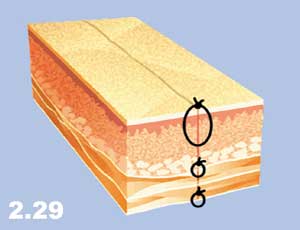

i) Tissue should be sewn layer by layer and each layer should be identified (Figure 2.29).

Operating Tissue Forceps #

Holding Tissue Forceps

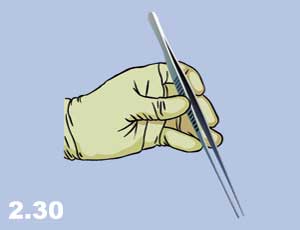

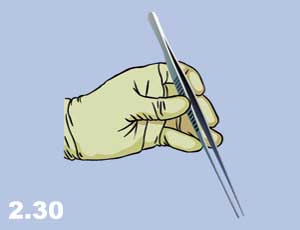

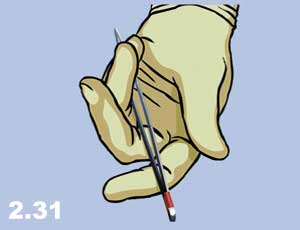

The best way to grip tissue forceps is to hold the forceps between the fingers in such a position that the thumb is on one blade and the index finger and third finger are on the opposite blade (Figure 2.30). This position, with the thumb against the index finger (metacarpophalangeal joint), gives the widest range of flexibility to maneuver the tissue forceps. When the tissue forceps are not in use, they should be held in the palm of the hand and secured with the little finger or ring finger (Figure 2.31). Figure 2.32 demonstrates an undesirable hold that restricts the maneuverability of the operator on all planes.

Using Tissue Forceps

Forceps are used for a variety of reasons in surgical procedures such as holding tissue during cutting, retracting for exposure, stabilizing during suturing, extracting needles, grasping vessels for cautery, passing ligatures around hemostats, packing sponges, or everting skin edges for clipping.

General Principles:

The most important principles for the proper handling of tissue forceps include:

a) Never keep inactive forceps in the palm of the hand as it restricts maneuverability.

b) When turning forceps from a passive position to an active position, hold the palm down as gravity aids the shift from a “hold” to a “use” position.

c) Do not keep elbows close to the body as this restricts mobility.

d) Do not crush and traumatize tissue with forceps.

Operating Clamps #

Holding a Surgical Clamp

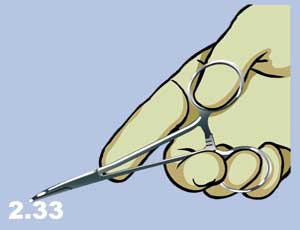

a) Thumb and Ring Finger. A surgical clamp is usually held like a needle holder or scissors with the thumb in one ring, the ring finger in the other ring, the third finger over the top of the ring and the index finger on the junction of the branches (Figure 2.33).

b) Thumb and Index Finger. The surgical clamp can also be held by entering the thumb into one ring, the index finger into the second ring, the middle and ring fingers on the back of the second ring, and holding the clamp in the palm of the hand (Figure 2.34).

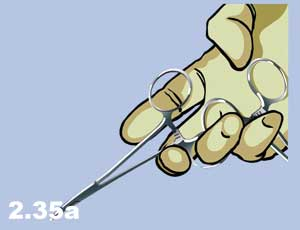

c) Multiple Holding. Sometimes multiple hemostatic clamps need to be applied. In this case, clamps are held in the palm and applied one by one (Figure 2.35a).

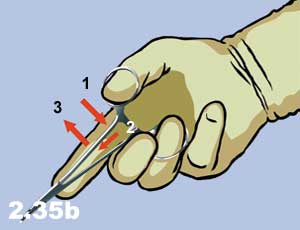

d) Classical Clamp Removal. For clamp removal, use the same grip as with the application of the clamp and remove by squeezing the ring and thumb fingers, and keeping the locking mechanism apart while opening the jaws. (Figure 2.35b).

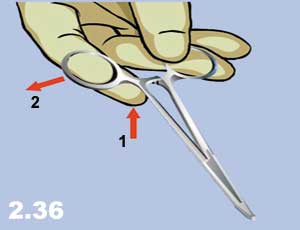

e) Other Techniques of Clamp Removal. Clamps can also be removed without having the fingers in the rings (Figure 2.36). In this technique, the left ring is pinched between the thumb and ring finger and the lock is disengaged by pressing the index finger beneath the opposite ring of the clamp.

Using a Surgical Clamp #

Using a Surgical Clamp

Surgical clamps can be used in many situations including hemostasis, dissection, retraction, holding the tissue, passing the ligature, and occlusion of tubular structures such as blood vessels, bowel or bronchioles. There are two methods to apply a hemostatic clamp:

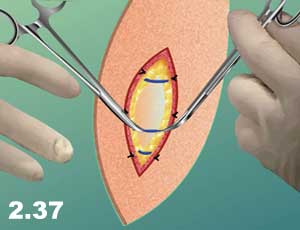

a) Apply on the dissected blood vessel before bleeding begins. In this case, two hemostatic clamps are applied proximal and distal to the target area and the vessel is cut between the clamps (Figure 2.37)

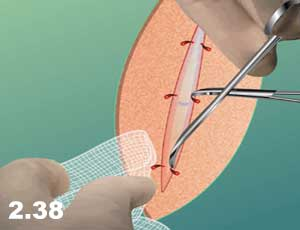

b) Trapping the bleeding vessel in the convexity of its jaw (Figure 2.38)

Ligation of a clamp takes several steps:

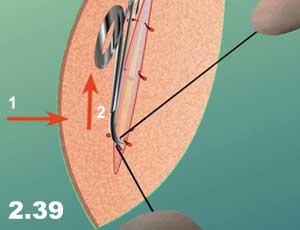

a) Hold the clamp upward and away from the tissue while the surgeon passes the ligature around the clamp (Figure 2.39)

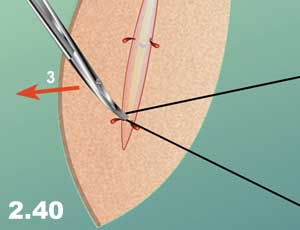

b) Lower the clamp parallel to the tissue to expose the tip (for surgeon to pass the ligature around to encircle completely (Figure 2.40)

c) Tilt the clamp slightly on its side in order to expose the side where the surgeon is tying the knot.

d) Slowly release the clamp as the surgeon tightens down the knot so that tissue does not slip before it is secured in the ligature.

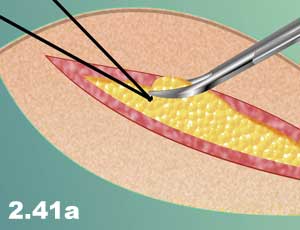

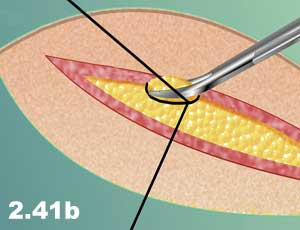

e) For additional security, one may suture under the clamp. Circle the first half of the clamp, and then the other half, before tying (Figure 2.41a and b).

General Principles:

The most important principles for the application and removal of surgical clamps are:

a) It is always a two-person job; it should not be done alone.

b) Before removing the clamp, make sure that the ligature is situated beneath the clamp.

c) Always remove the clamp slowly and with simultaneous tying of the ligature by a partner.

d) Never apply clamps blindly, clean the wound with sponges and/or suction in order to cause minimal trauma to the tissue.

Lecture on Demand