Description #

VCH Perioperative Program – clinical program. Required readings and post tests pertaining to the lecture for the surgical specialty of general surgery. The areas of clinical practice encountered during the clinical program and relevant to entry level perioperative nursing are: gastrointestinal, hernia, biliary (gallbladder), and breast surgeries.

Learning Objectives #

At the end of the session the nurse will be:

1. Prepared with information relating to the surgical specialty lecture topic by reading relevant materials

Gastrointestinal System Lecture #

Anatomy & Physiology of the Gastrointestinal (GI) Tract #

Your textbook does a good job of reviewing the basic anatomy and physiological functions of the GI tract. Do the following exercise to review: The GI system.

Reread unit PN 5 for a review of the layers of the abdominal wall. It is very important to understand the layers that the surgeon will be dissecting through and closing again at the end of the operation.

Functions of the GI System #

1) Digestion – Preparing food for digestion

- ingestion – teeth and tongue

- secretion – salivary glands, bile, pancreatic amylase, gastric juices – production of B12

- mixing and propulsion (peristalsis) – stomach, intestines

- mechanical and chemical digestion – alternating contractions and relaxation of smooth muscles in the walls of the GI tract mixing food and secretions that propel food toward the anus

- absorption – small intestines & large intestines (water) – passage of digested food and water from the tract into the cardiovascular and lymphatic systems and into cells

2) Elimination

- part of the digestive system serves as an organ of elimination for waste products

- defecation – large intestine, rectum, anus

The GI tract is the only system that is open to environmental influences. Skin is made up of a protective layer of keratin in its epithelium – the GI tract does not have this protection and so can be harmed by bacteria that are ingested (although there are some bacteria in the large intestine that aids in elimination).

Layers of the Intestines #

The GI tract is made of four layers or tunics.

The innermost layer is the mucosa, whose villi are responsible for the absorption of nutrients.

The second layer is the submucosa which consists of dense connective tissue. It binds the mucosa to the muscularis layer. It is highly vascular, contains autonomic nerves and is important in controlling secretions.

The third layer is the muscularis which is mostly smooth muscle tissue (the upper GI tract has some skeletal muscle which aids in the voluntary action of swallowing). The contractions of these longitudinal and circular smooth muscle fibers help to physically break down food, mix it with digestive juices, and propel the contents through the tract. It contains the major nerve supply (mysenteric plexus) of the GI tract as it controls GI motility.

The outermost layer is the serosa, a serous membrane. It is made up of connective tissue and epithelium. It makes up the viseral peritoneum which covers the organs and the parietal peritoneum which covers the abdominal wall – the space between the two makes up the peritoneal cavity. As one can see from the diagram below, the extent of peritoneal serosa can make a diagnosis of peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum) very serious.

We will now discuss some common pathologies of the upper and lower GI tract that require surgical intervention. For more detail on each of the procedures discussed, refer to your textbook for a detailed explanation of each surgical technique. The nursing interventions related to these surgical procedures will also be discussed.

Esophagus #

The esophagus is a collapsible muscular tube approximately 25 cm long. It lies in the mediastinum behind the heart and trachea and passes through the diaphragm at an opening called the esophageal hiatus. Although it is not long, it has a cervical, thoracic and abdominal portion.

It’s arterial blood is supplied by the inferior thyroid, thoracic aorta (aortic esophageal arteries), terminal branches of the bronchial, left phrenic and left gastric arteries. The venous supply is to the superior vena cava, azygous system, and left gastric vein – a branch of the portal vein. In portal hypertension these branches of the distal esophagus can form esophageal varices. It’s nerve supply is from branches of the vagus, laryngeal and cervical sympathetic chains.

The function of the esophagus is secretion of mucous and to be a tract to carry food to the stomach. The passage of food is regulated by:

- Food as it passes over the tongue, the soft palate and uvula cover the nasopharynx and larynx, which is pulled upward to meet the epiglottis to close off the glottis and entry into the trachea

- Contractions of circular and longitudinal muscle fibers (squeeze and shorten) to propel food toward the stomach, with the aid of mucous secretions. It does not produce enzymes and there is no absorption taking place in the esophagus.

- Swallowing cause the lower esophageal sphincter (gastroesophageal) to relax. Normal breathing causes the stomach to press up against the sphincter to prevent regurgitation.

Pathology of the Esophagus

Some common pathologies of the esophagus are:

- Strictures – narrowing of the esophagus caused by past surgery, chemical or thermal injury or anatomic anomalies

- Diverticula (Zenker’s diverticulum) – an outpouching in a hollow structure – usually occur in the cervical portion of the esophagus → dysphagia, regurgitation

- Varices – liver cirrhosis causes poor portal vein flow and backup of blood into the esophageal veins – can be treated by sclerosing (hardening) to strenghten. Rupture of varices is a medial emergency.

- Cardiospasm and achalasia – ineffective or absent peristalsis in the distal esophagus, persistent spasm

- Tumors – benign: common, leiomyomas, tumors of the smooth muscle

- Tumors – malignant – intervention is palliative and aimed at relieving dysphagia. Often cannot be successfully controlled, grow rapidly, are almost always fatal and often signs and symptoms do not show up until advanced stages when disease has infiltrated adjacent structures

- Hiatus hernia – defect in the diaphragm permits a portion of the stomach to protrude into the thoracic cavity at the hiatal opening. Symptoms vary from none → mild heatburn → reflux → dysphagia. Surgery is done only when symptoms are severe.

Surgery of the Esophagus

Diagnostic #

These procedures are typically done in an endoscopy unit, but may be done in the OR.

Esophagoscopy

One such procedure is esophagoscopy, typically done with a gastroscope (although an esophagoscope may be used – either a flexible or rigid variety). This procedure is mainly done for diagnostic reasons and/or for biopsy. It may also be done for removal of foreign body. This is considered a clean procedure. A light source is needed in addition to the gastroscope.

Esophageal Dilatation

This clean procedure is done to dilate strictures (from various causes) of the esophagus, increasing the lumen of the esophagus to ease dysphagia. It is done by passing Bougies (a long flexible solid tube) in progressively larger sizes (typically 24Fr-60Fr sizes) down the length of the esophagus to stretch the lumen. There are different types of bougies – some common ones are; mercury weighted, balloon and radio-opaque and guidewire directed (i.e. Savary- placed with the use of fluroscopy).

A complication of esophageal dilatation is perforation of the esophagus – a surgical emergency.

Open/ Laparoscopic Procedures of the Esophagus #

Open surgical procedures of the esophagus involve a transthoracic or a transabominal (or both) incision to access the esophagus portion that is to be repaired or resected. Although some of these procedures can be done as minimally invasive surgery (MIS) – i.e. hiatal hernia repair – most procedures of the esophagus are extensive, not only for the surgical procedure, but the postoperative course.

Stapling of Esophageal Diverticulum

To better understand the explanations of the following surgeries (and future units) – review PN 005 – Intraoperative Care Part 2 – Intraoperative Staplers.

A linear stapler (TA) is placed across the outpouch (diverticulum) to seal it off. The size of stapler used will depend on the size of the diverticulum. This procedure gives complete relief of symptoms.

Heller Cardiomyotomy

This is done for cardiospasm (the muscles of the cardia or lower esophageal sphincter) are cut, allowing food and liquids to pass to the stomach. It is used to treat achalasia, a disorder in which the lower esophageal sphincter fails to relax properly, making it difficult for food and liquids to reach the stomach.

A bougie is used to distend the esophagus, then a longitudinal incision is made through the muscular wall of the distal esophagus and proximal stomach leaving the mucosa intact. A fundoplication (see below) may be done at the same time to prevent gastric reflux. Heller cardiomyotomy is a myotmomy of the esophagogastric junction through a midline abdominal incision (xiphoid process to umbilicus).

Many surgical procedures are named after the surgical innovator of the procedure (i.e. Heller), sometimes a procedure will have a variety of names – a generic name if you will (i.e. Fundoplication) or go by a variation of the procedure perfected by a particular surgeon (i.e. Nissen Fundoplication). Every effort will be made to use the most commonly utilized form of a surgical procedure.

Esophagectomy/ Esophagogoastrostomy

An esophagectomy involves removal of the diseased esophagus (all or a portion) and the anastomosis of the remaining esophagus to the stomach. (esophagogastrostomy). It is done through a transhiatal approach with a neck incision; this is referred to as a 2-hole approach.

The factors influencing the type of approach will depend on the tumor site and the planned postoperative treatment (radiation or chemotherapy). Due to the approach being in the thoracic cavity, these surgeries are often done by a thoracic surgeon rather than a general surgeon.

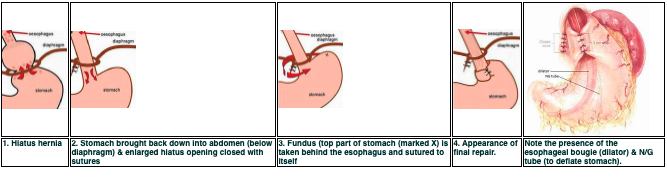

Hiatus Hernia Repair

A repair of a hiatal hernia involves correcting the diaphragmatic defect by restoring the cardio-esophageal junction to its correct anatomic position in the abdomen and therfore preventing the reflux of gastric juices into the esophgus. There are three common ways to repair a hiatus hernia, each hoping to draw the stomach back down into place and reinforce the closing function of the lower esophageal sphincter. An esophageal bougie is often inserted preoperatively in order to ensure that the repair is not done to tightly.:

- The Hill 180 – the upper part of the lesser curvature of the stomach is sutured to the median arcuate ligament

- Belsey – the stomach is aproximately 270 degrees around the esopageal circumference

- The most common procedure developed in the 1990’s for GERD disorder is the Nissen fundoplication – the upper portion of the stomach (fundus) is wrapped around the esophagus and sutured in place. This procedure is commonly done through a laparoscope and is pictured below.

Stomach #

Stomach #

The stomach is made up of five layers:

- Mucosa – innermost layer, where the stomach acid and digestive juices are made. Most of the time stomach cancers start in the mucosal layer. The mucosal layer appears as a series of folds or rugae, which allow the stomach to expand when full.

- Submucosa – supporting layer surrounded by the muscularis layer

- Muscularis – a layer of muscle that moves and mixes the stomach contents and propels them towards the intestines

- Serosa – outermost layer that that consists of connective tissue that is continuous with the peritoneum

The stomach is divided into the fundus (the upper portion of the stomach), the cardia (where the esophagus joins and empties into the stomach), the body or corpus (the main central region) and the pylorus or antrum (the lower section of the stomach that facilitates emptying into the duodenum).

Functions of the stomach include:

- The site where mixing of the saliva, food and gastric juice occurs. This is aided by the action of the circular, longitudinal and oblique muscle fibers of the muscularis

- Production and secrection of gastric juice, which is made up of hydrochloric acid (made by parietal cells), pepsinogen (made by the chief cells), intrinsic factor and lipase. Pepsinogen aids in the breakdown of protein by mixing with the hydrochloric acid it becomes pepsin and the mucous produced prevents the pepsin from acting on the protein of the stomach cells; if pepsin is not produced, then stomach ulcers can result.

- Allows for the absorption of Vitamin B12 (intrinsic factor)

The blood supply for the stomach is supplied by the celiac, right and left gastric and gastroepiploic arteries. The nerve suppy is from the paragympathetic vagus nerve and sympathetic nerves arise from the celiac ganglia

Pathology of the Stomach

The main causes of pathology to the stomach are:

- Ulcers are a break in the mucosa that leads to erosion of the muscle wall. It can sometimes extend into the peritoneum or even perforate into the perioneal cavity; which denotes an emergency situation requiring immediate surgery. Peptic ulcers are classified as gastric (in the stomach), esophageal or duodenal depending on the location. In the stomach, ulcers usually occur along the lesser curvature close to the pylorus. A common causative factor is infection by Helicobacter pylori.

. Eroding gastric ulcer

- Tumors are most common in people over 40 yrs old and early stages are often asymptomatic. The prognosis is often poor due to the presence of metastases due to late diagnosis. Most tumors of the stomach are adenocarcinomas (malignant lesions) that infiltrate the surrounding mucosa and penetrate the stomach wall and adjacent structures. The liver, pancreas, esophagus and duodenum are often affected. If a tumor is localized (in the stomach only), then a resection would likely be curative. In the presence of metastased and when a cure is unlikely, a subtotal or total gastrectomy may be done

- Pyloric stenosis is a condition that causes severe vomiting in the first few months of life. There is narrowing of the opening from the pyloric portion of the stomach to the intestines, due to enlargement of the muscle the pylorus, which spasms when the stomach empties. It is uncertain whether it is a congenital narrowing or whether there is a functional hypertrophy of the muscle which develops in the first few weeks of life.

Surgery of the Stomach

Open surgical procedures of the stomach are usually done with an upper midline incision. Although more and more procedures are being attempted as MIS approaches (i.e. a partial gastrectomy), as newer methods are developed these procedures are becoming more common.

A few of the more common surgeries are:

Gastroscopy

Gastroscopy is mainly done as a diagnostic procedure and may include biopsy. It may also be done prior to any of the procedures listed below, especially prior to a repair of an ulcer. This procedure, if not done in conjunction with an operative procedure, is usually done in an outpatient clinic under sedation. Prior to using the gastroscope it’s ports must be tested for adequate suction, ability to inject air (to distend the stomach for better visualization of the stomach or intestinal lining), ability to pass special flexible instruments through the channel, and that the light source is sufficiently strong. Go to the following webpage to view an animated version of a Gastroscopy.

Vagotomy

A vagotomy may be performed when medical management of peptic ulcers has failed – which is considered to be rare in present times. The procedure involves division of the vagus nerve, which causes a reduction in gastric secretion by interrupting the paraympathetic innervation involved in this process. This may be done using a thoracoabdominal incision, in order to retract the esophagus and obtain access to the vagus nerve.

There are three types of vagotomy (pictured below):

- Truncal – severing the nerve as enters abdomen, producing total abdominal vagal denervation and requires a drainage procedure to prevent gastic stasis (pyloroplasty). A posterior truncal vagotomy with anterior seromyotomy (incision into serosa and muscularis of the stomach) preserves the anterior vagal trunk and so does not require a drainage procedure.

- Selective – dissecting some branches of the vagus nerve, sparing the branches to the liver and small intestine but producing total gastric vagotomy; also requires a drainage procedure

- Parietal cell – identifying the small branches of the vagus nerve that only stimulate the parietal cells – which are responsible for hydrochloric acid production. Parietal cell vagotomy is the least disruptive to gastric emptying and leaves the pylorus sphincter function intact.

Complications of vagotomy include hemorrhage, obstruction caused by scarring or edema, and perforation.

Pyloroplasty

A pyloroplasty is the widening of the pylorus (distal end of stomach) and/or pyloric valve to create a larger opening between the stomach and the duodenum. This is done in patient’s with pyloric stenosis or patient’s at high risk for gastric or peptic ulcer disease (PUD). Also, patient’s who have had a vagotomy for PUD, will have slow gastric emptying and so a pyloroplasty is often done simultaneously. The surgery involves cutting through some of the thickened muscle to relieve the stenosis (narrowing) or removing the cicitricial (scarred) bands of the pyloric ring. The cut through the muscle is then closed horizontally to keep the pylorus open and allow the stomach to empty and reduce spasm.

An incision is made and then closed horizontally to widen the pyloric region.

Repair of Perforated Ulcer

A perforated peptic ulcer is an emergency procedure to stop the loss of blood and repair the perforated stomach. Control of bleeding may occur prior to surgery through an endoscope to cauterize, clip or inject the ulcerated area. The hole is then oversewn with nonabsorbable suture, patched with a piece of omentum, or the ulcerated area is resected and the hole closed up with suture or a linear stapling device.

Gastrostomy

A gastrostomy is the creation of a channel between the gastric lumen to the skin, usually so that a feeding tube can be inserted. It is either permanent (for pallative reasons) or temporary (for obstructions occuring proximally or distally to the stomach). It can be done as an open procedure or as a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube.

Gastrojejunostomy

A gastrojejunostomy is a permanently created communication (opening) between the jejunum and the stomach; providing a large opening without sphincter obstruction. It is done to treat benign obstruction at the pyloric end of the stomach and for when a partial gastrectomy is not feasible for inoperable lesions of the stomach. A gastrojejunostomy is usually done post partial gastrectomy (see below)

An upper midline/paramedian abdominal incision is used for open procedures or it may be done laparoscopically. A N/G tube is placed by anesthesia to deflate the stomach. After the stomach and small intestine are mobilized, a series of linear staplers are used to connect the stomach to the jejunum. A feeding tube may be placed to bypass the staple line until healing occurs (as leakage may occur through the staple line if it is not healed).

Gastrojejunostomy

Partial Gastrectomy

Removal of a portion of the stomach may be done to resect a benign or malignant lesion in the pyloric region or upper half of the stomach. An anastomosis is done between the stomach and the duodenum, this is called a gastroduodenostomy. This surgery is sometimes referred to as a Bilroth I procedure (when there is sufficient duodenum to reattach the stomach to).

Bilroth I

A resection of a benign or malignant lesion in the distal portion of the stomach (along the greater curvature of the body) requires an anastomosis between the remainder of the stomach and the jejunum; this is called a gastrojejunostomy. This was described above, however, when a portion of the stomach is removed and attached to the jejunum, it is often referred to as a Bilroth II procedure.

Bilroth II

These procedures are often done through a paramedian or midline abdominal incision. Postoperatively they are associated with the complications of:

- Dumping syndrome – the pyloric sphincter is removed and the stomach is smaller – feels fuller faster and can result in loss of appetite, weight loss and vomiting

- Vitamin B12 and iron deficiency which can cause anemia

- Afferent loop syndrome – the blind end of bowel (duodenum) still communicates and food that does not move along the tract properly becomes static allowing for bacterial growth, bloating, pain, diarrhea and fatty stools

- Stomal ulceration from the gastric juices

In order to prevent some of these symptoms a special reanastomosis for a gastrojejunostomy is done; called a Roux-en-Y. It was first described by Cesar Roux as a means to bypass the stomach, but has developed into a series of surgeries that use intestine to bypass (or re-route) food or GI secretions around a diseased or resected organ. Anastomosis of the distal divided end of the small bowel to another organ (i.e. stomach) and then a proximal end is anastomosed to the small bowel below the anastomosis – resulting in a “Y” shaped anastomosis). You will hear of this procedure in future units.

Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy: Duodenum remains intact allowing for the entrance of gasric juices, bile and pancreatic juices into the GI tract. The jejunum is resected and the distal end is reanostomosed higher onto portion of the stomach (a portion of the stomach has been resected and reanastomosed with the remainder of the stomach). The proximal of the jejunum is reanastomosed to portion of distal jejunum or ileum.It prevents the bile and pancreatic juices from entering the gastric remnant and prevents damage from the digestive enzymes, but at the same time allowing the enzymes to move naturally down the GI tract. It also helps prevent reflux esophagitis.

Total Gastrectomy

Total gastrectomy is the complete removal of the stomach. It is a potentially curative or palliative procedure to remove a malignant lesion and it’s metastases in adjacent lymph nodes. A more extensive resection of surrounding organs may be required, such as emoval of the spleen, pancreas, distal esophagus, duodenal cuff, omentum and adjacent lymph nodes. After removal of the stomach an anastomosis is done between the esophagus and the jejunum (esophagojejunostomy), as pictured below.

Bariatric Surgery

Surgery done to promote weight loss in the morbidly obese (BMI greater than 40) is referred to as bariatric surgery. There are two types of operative procedures:

- Restrictive: Involves the creation of a circular window through the proximal end of the stomach to reduce capacity. A specific procedure, often done laparoscopically, is called Vertical Banded Gastroplasty (VGB), where a portion of the stomach is stapled closed and a mesh band is inserted around a portion of the stomach. The smaller size of the stomach encourages the individual to eat smaller portions less frequently.

- Malabsorptive: These procedures involve a gastric bypass Roux-en-Y or a gastrojejunostomy. Reducing the stomach size and the amount of food absorbed promotes weight loss. These procedures produce a greater weight loss, but are not considered as nutritionally sound and are more invasive with greater complication rates.

Both surgeries rely on patient compliance to monitor eating habits and not exceed their new stomach capacity. These patients require special considerations not only for their emotional state, but for the physicality that they present. Large weight bearing capacity operating tables are required, as are longer instruments, larger BP cuffs and extra personnel for transfers.

Small Intestines #

The peritoneum consists of the parietal peritoneum, that which lines the abdominal walls; and the visceral peritoneum, which lines (coats) the internal organs. Two outward folds of the visceral peritoneum are the omentum and the mesentery.

Omentum

The omentum is a four layered fold (a double layer that folds back on itself) in the serosal of the stomach. It hangs over the large intestine and coils of the small intestine. It is like an apron made of fatty tissue and is very vascular. It is a protective barrier to the internal organs.

Dissecting the omentum (lifted up off of intestines)

Mesentery

The mesentery is an outward fan-shaped fold of the serous coat of the small intestine. It is an extension of the peritoneum. Blood vessels, lymph nodes and nerves are all contained within the mesentery. A tip of the fold of mesenteric tissue is attached to the posterior abdominal wall; anchoring the small intestine to the abdominal wall.

Pathology of the Omentum and Mesentery

Pathology associated with the omentum and mesentery are usually due to it’s close association with other organs, it’s high vascularity and numerous lymph nodes. The omentum is a often involved in some ovarian cancers. Also, if these structures are not properly dissected during the approach to the organs beneath them unnecessary bleeding and/or avascularity to these organs can occur. Any type of spillage of bowel can lead to an infection of the peritoneum and a very painful and serious peritonitis.

Surgery of the Mesentery and Omentum

Surgery of these structures generally involves dissecting through them to reach the organs beneath. Biopsy and/or removal of the omentum may occur during other procedures if metastatic disease is suspected.

These procedures involve careful dissection of the blood vessels contained within.

In this picture half of the omentum has already been dissected free of the stomach.

Two clamps are placed a short distance apart over a blood vessel. Then the vessel is cut between the two clamps. Then nonabsorbable suture ties (silk) are placed over the clamps and the vessels are ligated.

This may also be done with a stapling device or an instrument called an Harmonic scalpel (an ultrasonic heat sealing clamp).

Small Intestine

The small intestine is a 6.4 meter long and 2.5 cm in diameter. It’s blood supply is from the superior mesenteric and gastroduodenal (off the celiac) arteries and venous return is by the superior mesenteric vein (joining the splenic to become the portal vein). The nerve supply is from the superior mesenteric plexus.

Ninety percent of the food digestion and absorption occur in the small intestine. The intestines produce the intestinal enzymes lactase, maltase and sucrase. Along with the stomach acids, which are neutralized by the pancreatic enzyme (trypsin) that act in the intestine; other pancreatic enzymes and bile produced by the liver (stored and released by the gallbladder), the process of digestion can occur.

The small intestine is divided into three portions:

- Duodenum – shortest part, 25 cm long, begins at the pyloric sphinctor and merges with the jejunum

- Jejunum – 2.5 meters long and extends to the ileum

- Ileum – 3.6 meters long and extends to and joins the large intestine at the ileocecal valve

The mucosal layer has a series of villi or projections up to 1 mm high, which increase the surface area available for absorption.

The layers of the intestine, much like the rest of the tract, were discussed on the opening page of this unit.

The food in the tract is acted on by the enzymes and forms a substance called chyme. The chyme moves through the tract at about 1 cm per minute, remaining in the small intestine approximately 3-5 hours. With the aid of the muscular layer of the intestine, the chyme is propelled and hence aided to absorb by a series of movements:

- Segmentation – localized contraction in areas containing food. Contraction mixes food and digestive enzymes together.

- Pendular movement – alternating contractions propel food forward

- Peristalsis – propels food onward by a series of rhythmic pendular movements; as one section contracts the area after it relaxes, sending the food forward. These contractions are not as strong as the ones in the stomach or esophagus, but are very effective, as they allow for absorption to occur enroute.

Ninety percent of the food is changed into usable substances and are absorbed into the blood or lymphatic system and transported to the cells to use. Any unusable substances are excreted.

Pathology and Surgery of the Small Intestine

Disease of the small intestine is similar in nature to the large intestine, although there are some specific differences (i.e. Ulcerative colitis). The surgical approach to the small and the large intestines may vary, however, the surgical techniques used to resect and repair bowel are the same. The pathology and common surgeries will be discussed in the next section on the large intestine.

Large Intestine #

The lower gastrointestinal tract is referred to as the colorectal system. It consists of the large intestine, mesocolon, appendix, rectum, and anus. The function of the lower GI tract is the completion of absorption of digested food, especially water and minerals; and the compression of the waste into something that is easily expelled from the body. As the chyme moves through the large intestine, the water is removed and the chyme is mixed with mucous and natural gut bacterial flora, and converted into feces.

Mesocolon

The mesocolon is similar to the mesentery of the small intestine. It is an extension of the peritoneum and contains blood vessels, lymph glands, and nerves. It binds the large intestine to the posterior abdominal wall.

Mesocolon with enlarged lymph nodes

Large Intestine

The large intestine is 1.5 meters long and 6.25 cm in diameter. It extends from the ileum (ileocecal valve) to the anus. It’s blood supply is from the mesenteric arteries and the nerve supply is the sympathetic celiac, inferior and superior mesenteric and the internal iliac plexus, and the paraympathetic vagus and pelvic splanchic nerves.

The large intestine is made of three bands of longitudinal muscle fibers which are slightly contracted and divide the intestine into pouches (haustra). After all nutrients have been absorbed from the small intestine, the now watery mass passes into the large intestine. The peristaltic rate is slow, and unlike the small intestine which has irregular waves, peristalsis in the large intestine is continuous. Two to three times a day, the gastrocolic reflex (due to the presence of food in the stomach), creates a massive peristaltic wave that starts in the middle of the transverse colon and ends at the rectum – propelling material towards the rectum and anus, this may trigger the need to defecate in some individuals.

The large intestine is divided into four sections:

- Cecum – blind pouch 6 cm long; appendix is attached; merges with the colon

- Colon – divided into ascending (ascends to right side of abdomen, reaches under surface of the liver and turns to the left – turn is called the hepatic flexure); transverse (continues across the abdomen and curves beneath the spleen – curve is called the splenic flexure); descending (passes downward to the level of the left iliac crest); and sigmoid (begins at the left iliac crest, projects inward to the midline, terminates at the rectum – at the level of the 3rd sacral vertebra)

- Rectum – last 20 cm of tract

- Anal Canal – last inch of the rectum; contains a network of arteries and veins; anus is the external opening; has an internal sphincter (involuntary smooth muscle) and an external sphincter (skeletal muscle) that is under voluntary control

Pathology of the Large (and Small) Intestine

As mentioned before, the pathology of the large intestine is similar to the small intestine. Most of these pathologies lead to bowel obstruction and potential rupture, bowel strangulation (the cutting off of blood supply and leading to bowel necrosis), or bowel incarceration (bowel is trapped and if not reduced back to normal position can lead to strangulation or rupture). Common pathological causes for surgical intervention include:

Surgery of the Large (and Small) Intestine

Bowel resection is the main surgical procedure to treat bowel obstruciton, bleeding, ischemia, tumors or disease. The resection may be done as an open procedure or ,as is becoming more common, laparoscopically.

Laparoscopic bowel resection

Removal of up to 50% of total bowel is well tolerated. Resection margins are based on lesion location, lymphatic drainage, and blood supply to the portion of affected bowel. It is necessary to remove a portion of healthy tissue around the lesion to ensure that all of the disease is removed (resection margin, margin of safety). After resection is complete, a form of bowel reanastomosis is done to maintain bowel continuity.

Sometimes advanced inflammation or trauma can lead to bowel distention or obstruction and so a temporary decompression of bowel or diversion of contents may be performed to promote healing. An opening into the ileum – an ileostomy and formation of a stoma – may be done to divert contents and reduce activity in the colon in order for it to rest and promote healing. A colostomy – opening into the colon and formation of stoma – may be performed for the same reasons.

Right Hemicolectomy

Removal of tumors or obstructions in the ileocecal, ascending and proximal transverse colon are achieved through a right hemicolectomy. The entire ascending colon must be removed due to the blood supply to this portion of bowel; a partial resection would end in ischemia.

Before After reanastomosis

A temporary colostomy may be performed if there is a need to rest the bowel, or as seen in the right hand picture above; bowel continuity is maintained by a reanastomosis of ileum to the remainder of the colon. This is achieved by the use of two cartridges in a linear (GIA) stapler – one on either side of the obstruction to resect the diseased bowel. Another cartridge is used to perform a side-to-side anastomosis (pictured below) of the ileum and colon. A different stapler – a TA stapler will be used to close off the hole made by this GIA stapler.

It is important to review PN 005 – Intraoperative Care Part 2 – Intraoperative Staplers to truly appreciate how surgery of the bowel is performed.

Left Hemicolectomy

Removal of tumors or obstructions in the distal transverse, splenic flexure, descending and upper sigmoid colon are done with a left hemicolectomy. The same technique is applied as for a right hemicolectomy.

Before. After reanastomosis

Hartmann’s Resection – this procedure is somewhere between a left hemicolectomy and an anterior resection. If a portion of the rectum and lower colon have not been removed, then two options are available. The distal portion can remain sealed off and the proximal end is brought out as a colostomy. Since the lower bowel is still present, the patient may still feel the need to defecate. If the colostomy is temporary, once healing of the lower bowel has occurred, another operation is required to reanastomosis the two ends of bowel and the colostomy site incision is closed.

Hartmann’s resection

Anterior Resection

An anterior resection removes lesions in the lower sigmoid and rectosigmoid colon – lesions can be as low as 5 cm into the rectum.

This procedure allows for an end-to-end anastomosis of the colon and rectum (with an EEA stapler). As the EEA stapler can be inserted externally through the anus up into the rectum; it allows for as close to a normal reapproximation of bowel continuity.

EEA stapler in action

The patient may have a temporary ileostomy to protect the anastomosis by bypassing and resting the colon.

This procedure requires two set-ups of sterile instruments – one for the abdominal portion and one for rectal stapling (considered the “dirty” part of the procedure) – this prevents contamination of the abdomen from any fecal matter. The surgery is done in a modified lithotomy position in order to have access to the rectal area. Preoperatively a urologist may insert ureteral stents into the ureter (by performing a cystoscopy) – this will allow the surgeon to identify the ureter (by feeling the stiff stent within it) and due to it’s close proximity, not damage it during dissection of the sigmoid bowel.

Abdominal Perineal Resection

An abdominal perineal resection is done for tumors that are too low to be reanastomosed with an EEA stapler (i.e. less than 5 cm into the rectum). This surgery also requires two set-ups: an abdominal portion and a perineal portion (unlike the anterior resection, this set-up requires some instruments and an ESU). After the resection, the proximal bowel is brought out and a colostomy is formed. The rectal remnants are brought out through the anus and then the perineal area is sutured closed. Like the anterior resection, the patient is in a modified lithotomy position and urological stents may be inserted preoperatively.

Proctocolectomy

A proctocolectomy is the removal of the entire colon and rectum, leaving only the anus intact. This is the surgery of choice for chronic repetetive ulcerative colitis resections and for familial polyposis. The patient losses the ability of transanal defecation and so a permanent ileostomy is created. Another option over an ileostomy, is the creation of a pelvic pouch, which is an internal reservoir made of small bowel. The patient uses an in and out catheter to flush out the contents on a daily basis.

Proctocolectomy

Stomas

Besides the site of the colostomy (i.e. ileostomy, colostomy), there are different kinds, depending on how the bowel is brought through the small incision externally and sewn to the skin. The stoma site is important for viablility and functionality for the patient.

Colostomy

They also may be designed to be permanent or temporary. The fecal content an odor between an ileostomy (watery appearance) and a colostomy (somewhat formed) are very distinct. The following picture describes the different types.

All stomas require an appliance or bag to capture the contents.

Selection of colostomy bags with adhesive

Complications of stomas include:

- Early: mucosal sloughing/necrosis due to poor blood supply; obstruction due to edema of fecal impaction; persistent leakage causing skin erosion due to inappropriate location

- Late: prolapse; parastomal herniation; parastomal fistula; retraction of spout ileostomy; stenosis; perfroration post irrigation; psychological and psychosexual problems

If a patient comes to the OR with a stoma, the appliance must be removed and during the skin prep the stoma may be covered with a sterile gauze, areas around the stoma are prepped, and then the gauze is removed and the stoma is prepped last.

Postoperatively an appliance must be available to place over the stoma to protect the incision site from contamination.

Appendix, Rectum and Anus #

Appendix #

Pathology of the Appendix

The vermiform appendix is a blind-ended tube off the cecum, which is the embryonic orgin of the cecum. It is thought to have no function other than than being the orgin of the cecum, but some feel that it may harbor and protect bacteria that are beneficial to colon health. However, people who do not have an appendix are not considered to be at a health disadvantage, hence the feeling that it no longer serves a purpose in adults.

An inflammation of the appendix results in appendicitis, a life threatening condition if the appendix ruptures leading to peritonitis and sepsis.

It is usually caused by obstruction due to a fecolith, which leads to inflammation, infection and necrosis from hypoxia.

Inflammed appendix

Surgery of the Appendix

The appendix may be removed either via an open procedure, which is very rare and would most likely be done if the patient had serious adhesions or perhaps rupture. The most common way to remove the appendix is laparoscopically. The other advantage that the laparoscopic approach has, especially in women, is that a general viewing of the entire abdomen can be achieved and other sources of pain ruled out (i.e. gynecological disease). It is important for the patient to void prior to laparoscopy to ensure that a full bladder does not impair the view or place itself in harms way; for an open procedure a catheter may be placed. Both procedures are done in the supine position.

Open Appendectomy

Rectum and Anus #

Pathology of the Rectum and Anus

The pathology related to the rectum was discussed in the previous page, as regards to tumors of the sigmoid colon and rectum.

Other problems that require surgical intervention are:

- Prolapse – the intussesception of the rectum into the anal canal.

This is more common in women; and in some women who have had a hysterectomy, multiple births, or a traumatic labor can be prone to rectocele – a herniation of the rectum into a weakened or torn vaginal wall. A rectocele repair is usually done by a gynecologist and will be discussed in the gynecological surgery module.

- Hemorrhoids – dilated veins in the anal region, can be internal or external. Symptoms include pain, bleeding, and hemorrhoidal prolapse during defecation. The pectinate (dentate) line divides the anal canal, delineating two different areas containing different tissue and structures. External hemorrhoids are a venous plexus below the pectinate line that is covered with squamous epithelium. Internal hemorrhoids occur above the dentate line and are submucosal vascular tissue that contain muscular and connective tissues. The result of the presence of the hemorrhoids is the same, but the amount of vascularity and tissue type differs.

- Fissures – epithelial defects, tears, ulcerations in the anal canal, extension of Chron’s disease or viral disease. Fissures are painful and can lead to infection or fistulas.

- Fistulas – a communication between two organs or from an internal organ to the external surface of the body – and is described by the communicating parts (i.e. anovaginal – tract between the anus and vagina). Usually resulting from perianal abscesses or ulcers. Classified according to their relation in location to the sphincter mechanism. The primary opening is readily found if an external opening is actively discharging purulent material. Probes are used to find the fistual tract – length and direction – or a dye may be injected.

- Perianal Infections – appear as indurated, erythematous areas adjacent to the anus and originate from the anal glands and are due to the presence of enteric flora. If left untreated, abscesses will develop and require an incision of and drainage of the abscess. This is not a pilonidal disease.

- Pilonidal Sinus – an infection that originates in the gluteal cleft from a hair follicle that penetrates the skin and leads to chronic abscess formation.

Surgery of the Rectum and Anus

Surgery of the rectal or anal area is done in the lithotomy position or for some surgeries (i.e. pilonidal sinus) in the prone position. Patient’s will undergo a bowel prep preoperatively. It is essential to have some lubricant (i.e. Muko) for scopes or retractors to prevent mucosal damage during their insertion into the anus.

Diagnostic Procedures

Sigmoidoscopy and colonscopy are used diagnostically to view the colon and check for the presence of diverticula, polyps, ulcerations, etc. A sigmoidoscope may be of the rigid variety or flexible, depending on what the surgeon wishes to view. Typically it is possible to see halfway up the descending colon with a flexible sigmoidoscopy. The whole colon can be viewed with a colonoscope. Along with a good light source, like the gastroscope, these scopes have the ability to introduce air in order to expand the colon and enhance visualization. Biopsies may be taken using a wide variety of long instruments and biopsy forceps (flexible or rigid) designed to do so. A lubricant is used to easily insert the scopes.

Hemorrhoidectomy

The removal of hemorrhoids depends on the type and location and whether they have not responded to conservative treatment (i.e. stool softners). Usually an anal retractor is placed and the hemorrhoids are either injected with a sclerosing (hardening) agent; or snared and a small rubber band is placed to cut off blood supply and eventually sluffs off with the hemorrhoid; or a device is used to heat and shrink the hemorrhoid. All of these are done in outpatient clinics. If the hemorrhoid does not respond to any of the above, surgery is done, and the hemorrhoid is clamped, tied off and cut away or a harmonic scalpel (ultrasonic type cauterization) may also be used.

Fissure repair/ Fistulectomy/ Perianal abscess drainage/ Pilonidal sinus removal

All of these procedures involve finding the sinus tract and excising it or removing infected or damaged tissue (debridement). Often the excised area is left open, rather than sutured closed, in order to heal by secondary intention, preventing recurrence. For a dressing, a length of packing is usually inserted into the wound, which the patient will change frequently postoperatively.

Perioperative Nursing Consideration for GI Surgery #

The following is an overview of nursing preparation and considerations for patients undergoing a gastrointestinal (GI) procedure. It will detail preoperative nursing considerations specific to GI surgery, rather than reiterate the general Perioperative nursing considerations learned in previous modules (please review PN 003 – Preoperative Care). The same detail will be given for all categories of consideration, as the following is meant to highlight what is unique to general surgery, rather than repeat the principles and information learned in PN’s 001-005).

GI procedures are generally considered to be major surgery, excluding anal and rectal procedures, whether they are done as an open procedure or laparoscopically. Any laparoscopic (MIS) procedure can run into unanticipated problems and convert into an open procedure.

Regardless of age or medical history, most patient’s will require the following nursing considerations:

Preoperative Care #

- Laboratory results – INR, hemoglobin, kidney function

- Ensure patient has voided if they are having a shorter laparoscopic procedure where a catheter may not be required (i.e. young adult having a laparoscopic appendectomy)

- Catheter insertion to monitor output

- Consent for a possible open procedure, if patient is scheduled for a laparoscopic procedure

- Calf compressors for procedures over an hour

- Gelpad or foam on OR table for procedures over an hour

- Correct OR table – i.e. ablility to fit stirrups if patient is to be in lithotomy position

- Insertion of ureteral stents for identification of ureters introperatively for complicated bowel resections – prepare for cystoscopy (OR table, stirrups, light source, drainage receptacle, irrigation)

- Set up forced air warming blanket – upper body warmer is best

- Order a postoperative ward bed for patients having esophageal, gastric or intestinal procedures

Anesthesia #

- General anesthesia for most procdures

- Patient’s with hiatus hernia at risk for aspiration – cricoid pressure

- Epidural anesthesia may also be given (inserted prior to general) for longer complicated procedures (i.e. bowel resection) for postoperative pain control

- Insertion of large bore IV – CVP and arterial lines for cases with expected blood loss, long procedures or if medically indicated (i.e. cardiac history)

- Setup and use of IV fluid warmer

- Insertion of N/G tube to decompress stomach

- May need to order blood

Positioning #

- Supine – stomach, bowel resection. Usually one arm on armboard and other arm tucked at side. There will probably be a self-retaining retractor used that attaches to the OR table, ensure that there is not any sheet or cords running along the OR table rail

- Lithotomy – anterior resection, abdominal perineal, hiatus hernia repair, rectal and anal procedures

- Lateral – esophageal procedues for part of the procedure and then supine for the rest

- Prone – anal and pilonidal sinus procedures

Skin Prep and Draping #

Skin prep:

- Abdominal prep with parameters of nipple line to groin; bedline to bedline

- Anterior resection and abdominal perineal procedures require an abdominal prep and a perineal prep (separate prep trays)

Draping:

- Supine and prone position is with 4 square/utility drapes and a laparotomy drape

- Lithotomy position requires leggings to cover the stirrups and a split sheet or laparoscopy drape to cover the abdomen

Equipment/ Instruments/ Supplies #

Equipment:

- Headlight – surgeon’s often looking into a deep cavity

- ESU and/or harmonic scalpel

- MIS tower (light source, camera, monitor, CO2 insufflator) for laparoscopic procedures

- Fluid warmer

- Forced air blanket warmer

- Availability of equipment/ stapling devices – if unavailable, intraoperatively is not the time to find out

Instruments:

- Major general instrument pan

- Bowel clamps

- Intraopertive staplers and sizers for the EEA stapler (to determine which diameter of stapler fits best into the rectum)

- Large multi-piece self-retaining retractor – Omnitract or Thompson or Bookwalter or occasionally a Balfour. Have surgeon double glove when attaching post to side rail of OR table and discard glove after post tightened (often will need to reach below the sterile field)

Thompson retractor

- Poole suction to irrigate – multi holes on suction to avoid suctioning right on bowel

- Count Procedures: A full instrument count is done for all abdominal procedures, whether done open or laparoscopically. If the procedure was completed laparoscopically, then there is no need to do an instrument count out (as the only peritoneal openings are small cannula/ port holes). Instruments are not counted for fistulectomy or or other anal type procedures. The exception to this is when a handport device is used – the hole to place this is much bigger than a cannula incision hole – so a full instrument count must be done at peritoneal closure.

- Bowel technique: Any instrument that has been used inside of bowel (i.e. Poole suction to aspirate contents, GIA stapler) must be considered contaminated. The surgeon will pass back the instrument and it should either be removed from the sterile field entirely or be placed in a basin that will contain the dirty instruments – do not reach into basin or touch these instruments for the rest of the procedure. Ensure that each item in the basin is visible as both the scrub and circulating nurse must be able to view items during the instrument count out process. It is not necessary to redrape or regown after the “dirty” instruments have been used, unless it has touched the drape or someone’s gown. The surgeon may wish to change gloves.

Supplies:

- 2-0 and 3-0 silk ties, 3-0 Vicryl reel

- GI needles is a common term given to 1/2 circle fine taper needles that are used on bowel and creation of stomas

- Skin incisions are usually stapled. Occasionally the patient may have a wound that may be under some tension and so a heavy reinforcing suture is placed deeply within the muscles and fascia of the abdominal wall to relieve the tension on the underlying sutures and avoid wound dehisence – the surgeon may use a heavy (2 Nylon) and close with interrupted stitches with a “bolster” threaded onto each stitch to protect the skin from the pull of the suture. This is called a retention suture.

- Warm irrigation fluid – surgeon may wish to irrigate with sterile water in cancer patients (water causes hemolysis of any stray cells)

Surgical Incision #

- Esophagus – 2 hole or 3 hole – thoracoabdominal and midline

- Stomach – upper abdominal midline

- Bowel – midline or paramedian for bowel resection

- Appendix – McBurney’s

- Laparoscopic approach – 3 to 5 cannula/port incision holes

Specimen Care #

- Resected tissue – some may be for frozen section

- Anterior resection – resected bowel from stapling – “donuts” are checked that they are uniform in shape, indicating a secure staple line that will not leak

- Culture and sensitivity – swabs sent for perianal abscess, fistulas, appendicitis

Dressings and Drains #

- A strip dressing is sufficient for most procedures; abdominal pad may be required

- Steristrips and bandaids for laparoscopic port holes

- Stoma appliances for ileostomy or colostomy

- Strip packing for fistulectomy

- Flat hemovac drains may be inserted for bowel resections; chest tube may be inserted for esophagectomy if pleural cavity entered

Hernia Lecture #

Hernias have been discussed as far back in history as in the times of Babylon, and in 2800 BC the first physcian treatment of a hernia was reported. What is a hernia?

A hernia is a protrusion of a tissue, structure, or a part of an organ through the muscle tissue or the membrane by which it is normally contained. Although herniations can occur anywhere (i.e. hiatus hernia – stomach into the esophagus through hiatal opening), the term usually refers to identifying hernias of the lower torso or abdominal wall hernias.

Acquired vs Congenital #

Hernias can be either acquired or congenital. Abdominal hernias can be present at birth, others develop later in life, either by pathways formed during fetal development, existing openings in the abdominal wall, or in areas of abdominal wall weakness. The anterior abdominal wall is made of several layers and structures – these include:

Acquired hernias develop through the weakness in the abdominal wall or are created (or are exacerbated) by:

- Obesity, poor nutritional status

- Heavy lifting

- Excessive coughing and/ or chronic lung disease

- Straining during defecation or urination

- Fluid in the abdominal cavity (i.e. ascites)

- Previous surgery

- Age, gender (males more likely to have inguinal hernia)

- Family history increase the chance for hernia development

The hernia mass is composed of:

- The orifice through which it herniates (i.e. muscle)

- The hernial sac in which it is contained (i.e. peritoneum)

- The contents (i.e. intestine)

Signs and Symptoms #

The signs and symptoms of the hernia will differ depending on whether the hernia is reducible, irreducible or strangulated.

Reducible

The contents of the hernia sac can be returned to the normal intraabdominal position – either manually or when the precipitating factor is removed (increased abdominal pressure – coughing, straining). It may ache but usually is not tender when touched. The lump (hernia sac) becomes larger when standing or when intraabdominal pressure increases.

Irreducible

Contents are trapped extraabdominally and the sac cannot be reduced. Often referred to as an incarcerated hernia. It may be that an occasionally painful reducible hernia has now enlarged (or adhesions developed) and cannot be returned to it’s intraabdominal position. May persist longterm without pain, but can develop into signs and symptoms of bowel obstruction (abdominal pain and distention, nausea, vomiting). It can also lead to strangulation. A hernia that was irreducible, but resolves (has been reduced), has a high chance of recurring and becoming irreducible again – patients are often scheduled for elective surgery.

Strangulated

An incarcerated hernia becomes strangulated when the blood supply of the trapped sac contents is compromised. This leads to necrosis and constitutes a surgical emergency to save the viscera within the sac. Patient experiences persistent pain and often presents with signs and symptoms of a bowel obstruction.

Bowel is trapped through a muscle in the abdominal wall and has become ischemic (dusty blue indicative of hypoxia)

It is important to note that not all strangulated hernias are irreducible and that not all irrecducible hernias are strangulated.

Hernia Classifications #

Hernias are usually classified by their location on the abdominal wall. There is another type of hernia – a sliding hernia – in which the wall of the viscus (any large interior organ in any body cavity) forms a portion of the wall of the hernia, as it slides up . The most common sliding hernias involve the bladder, cecum, sigmoid colon or hiatus (stomach into the esophagus). Hiatus hernias were discussed in the previous section under GI surgery, and the others will be discussed in the section of gynecological surgeries (i.e. rectocele, cystocele). The different types of abdominal wall hernias are:

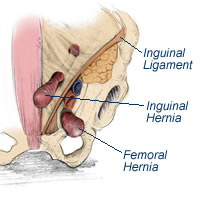

Direct vs Indirect Inguinal Hernia #

In the lower abdominal wall the transversalis fascia (a thin aponeurotic membrane) lies between the transversus abdominis muscle and the extraperitoneal fat. The spermatic cord in males and the round ligament in females pass through the transversalis fascia at the superior lateral area, called the abdominal internal (deep) inguinal ring. In the inferior medial area the transversalis fascia attaches to Cooper’s ligamment – the insertion point to the symphysis pubis. The deep internal ring is edged laterally by the epigastric vessels. As the canal passes through the abdominal wall, it is surrounded by the apeuronoses of the internal and external obliques and cremaster muscles, which form the superior inguinal ring, which opens superior and medial to the pubic tubercle.

The inguinal canal contains the spermatic cord and its associated blood vessels. The testicle starts out embryologically up near the kidney and as the fetus develops, it migrates from the abdominal cavity through the abdominal wall via the inguinal canal into its final resting place in the scrotum. This membranous connection to the peritoneal cavity is called the processus vaginalis; and if it remains patent after birth can lead one to be susceptible to indirect inguinal hernia development. In females it is along the round ligament (attached to the uterus) from the deep internal ring.

Indirect hernias leave the abdominal cavity at the internal ring and pass with the spermatic cord down the inguinal canal, lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. They often contain a sac (contained in peritoneum) and can be found in the scrotum. They have the potential to become strangulated.

Indirect inguinal hernia

Direct inguinal hernias occur within Hesselbach’s triangle – formed by the deep epigastric vessels laterally, the inguinal ligament inferiorly and the border of the rectus abdominus medially (pictured below).

The direct inguinal hernia bulges through the posterior wall of the inguinal canal medial to the inferior epigastric artery, posterior to and separate from the spermatic cord. Direct inguinal hernias present as a bulge and are not within the scrotum. They are brought on by heavy lifting, strenuous activity, muscular atrophy (related to age, disease or obesity), ascites, chronic cough, or ineffective repair of a previous hernia.

Knowing the difference between the two types is mainly related to diagnosis, however, knowing the cause will affect the difficulty, the approach and the type of repair that is performed.

Femoral Hernia #

Femoral hernias are visible below the inguinal ligament as the peritoneal sac passes under the liganment into the femoral canal – rather than into the inguinal canal. They are more common in women. They occur when the transversus abdominus aponeurosis and its fascia are only narrowly attached to Cooper’s ligament; the femoral ring is enlarged and the canal dilated. The ileofemoral vessels are prominent and need to be protected during repair.

#

#

Epigastric hernias can appear spontaneously or after previous operations – called incisional hernias. The anterior abdominal wall is composed of the external oblique muscles that are attached to a thick sheath of connective tissue called the rectus sheath.

#

The linea alba (white line) is a seam up the midline of the abdomen that extends from the xiphoid to the symphysis pubis. It is formed by fibers of the aponeurosis of the right abdominal muscles intertwined with the fibers of the aponeurosis of the left abdominal muscles.

#

Hernia Repair #

The following discussion refers to abdominal wall hernias only – for discussion regarding hiatus hernia and other sliding hernias, refer to the appropriate PN unit.

The term used for surgical repair of a hernia is herniorraphy. Repair of all types of hernias follow these main steps:

- Identification of hernia – location, contents, contained within a sac (peritioneum)

- Reduction of sac and contents (whether sac is opened or not), contents must be pushed back into their anatomical location.

- Evaluation of whether reduced tissue is viable. If not – as may be the case in strangulated bowel – a bowel resection and reanastomosis is performed prior to the hernia repair. Peritoneal sac is closed off (i.e. with a purse string suture) – any trimmed off sac is sent to pathology.

- A method for reinforcing the abdominal wall (hernia repair) is performed to prevent recurrence. If sufficient fascia exists on either side of the defect then it can be repaired with nonabsorbable suture. However, it is more common (especially in inguinal hernia repair) to reinforce the defect, by laying a specially designed mesh over the defect and suture into place.

Inguinal and hiatus hernias can be repaired either by the open method or laparoscopically. Other types of hernias are done via the open method.

Open vs Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair #

Repair Materials #

Suture

The types of suture material used for hernia repair are nonabsorble, monofilament, and at least size 0 or 1 in gauge and they are placed using interrupted stitches. Typical sutures used are Polypropylene (Prolene) or Polyester (Ethibond or Mersilene). Different techniques involve suturing the fascia closed, or suturing it to muscle or different ligaments (i.e. Cooper’s ligament) or structures – some common names for these inguinal hernia techniques are McVay, Shouldice and Bassini. The surgical approach, equipment and setup is the same for all techniques and all types of hernias.

Mesh

The insertion of mesh either under, over, or both is used to cover the defect and not only provides less tension (tension-free or tension-eliminating) on the repair, but provides fibrovascular growth within the pores of the mesh which increase the strength of the repair. The mesh itself is considered a foreign body and as such the body can react to it and increase the risk of infection.

An ideal implant/ prosthesis or in this case mesh should:

- Not be modified by tissue or fluids

- Be chemically inert – not excite inflammatory or foreign body reaction

- Be nonallergenic or cause hypersensitivity

- Be noncarcinogenic

- Be capable of resisting mechanical strain – strong enough to resist maximum forces placed upon it (i.e. intraabdominal pressure)

- Be constructed in a way that cutting it or passing sutures through it does not cause it to fray

- Be able to submit to a sterilization processes

- Be permeable and allow tissue ingrowth within it and stimulate fibroblastic activity to allow for incorporation into tissue rather than cause encapsulation

- Be pliable so as not to cause stiffness or be felt by the patient

The most common types of mesh used for hernia repair are made of Gortex, Marlex or Polypropylene (Prolene). They vary in shape and size, and are trimmed to fit.

Marlex mesh: inguinal patch with hole for spermatic cord and tails to secure around it (pictured); and inguinal hernia plugs.Placement of the mesh and meticulous suturing (or stapling) to secure it is a must, because if the hernia should recur, it is very difficult to remove without compromising surrounding tissue, and makes future repair more difficult. Stapling devices (Protack®) fire off staples that are more like short coils (~3mm) than staples – that spin into the mesh and underlying tissue and hold it securely in place.

Complications of Hernia Repair #

Complications of hernia repair include:

- Recurrence of herniation

- Urinary retention

- Wound infection

- Fluid buildup in the scrotum (hydrocele formation); scrotal hematoma; testicular damage on the affected side – after inguinal hernia repair

- Nerve irritation

Perioperative Nursing Considerations for Hernia Repair #

Preoperative Care #

- Laboratory results – basic lab testing – hemoglobin and ECG for patients over 50 years of age

- Ensure patient has voided if they are having a laparoscopic procedure. Most patients will go home the same day for inguinal hernia repairs, so a catheter is not needed. Patients having complicated (i.e. epigastric hernia) or emergency (strangulated bowel) repairs require a catheter, as it is still considered abdominal surgery.

- Consent for a possible open procedure, if patient is scheduled for a laparoscopic procedure

- Consent must be specific for left or right inguinal hernia – site must be marked

- Calf compressors for procedures over an hour

- Gelpad or foam on OR table for procedures over an hour

- Regular OR table for supine position

- Set up forced air warming blanket – upper body warmer is best

- Order a postoperative ward bed for elderly patients staying in hospital – judgement call

Anesthesia #

- General anesthesia (for all laparoscopic procedures); spinal anesthesia for hernias below the umbilicus; or local anesthetic injected prior to the skin incision

- Insertion of regular IV – CVP and arterial lines for emergent cases if medically indicated (i.e. cardiac history)

- Blood loss is minimal

Positioning #

- Supine

- Depending on location of hernia – either both arms out on armboards, or just one with the other tucked at side

Skin Prep and Draping #

Skin prep:

- Depends on location of hernia

- Abdominal prep with parameters of nipple line to groin; bedline to bedline for epigastric and umbilical hernias. For inguinal hernia prep – start at operative site (side) and prep past midline, up to and past umbilicus, to mid thigh, and perineum area.

Draping:

- 4 square/utility drapes and a laparotomy or pediatric sheet.

Equipment/ Instruments/ Supplies #

Equipment:

- ESU

- MIS tower (light source, camera, monitor, CO2 insufflator) for laparoscopic procedures

- Forced air blanket warmer

- Availability of stapling devices and mesh – if unavailable, intraoperatively is not the time to find out

Instruments:

- Major general instrument pan for epigastric, incisional and umbilical hernias. Minor general instruments for inguinal hernias

- Count Procedures: A full instrument count is done for all abdominal procedures, whether done open or laparoscopically. If the procedure was completed laparoscopically, then there is no need to do an instrument count out (as the only peritoneal openings are small cannula/ port holes). Instruments are not counted out at closure for inguinal hernia repair if the peritoneal sac was not opened.

Supplies:

- 1 or 0 nonabsorbable suture – i.e. Prolene

- Mesh – comes in a variety of sizes and shapes – use the smallest piece necessary (leftover should not be resterilized). Document on chart or implant record – size, type, manufacturer number, lot number and expiry date.

- Local anesthetic – Bupivicaine 0.25% with or without epinephrine

- 1/4″ Penrose drain (moistened) to pass around spermatic cord and gently retract out of the surgical field

Surgical Incision #

- At the site of the hernia

Inguinal hernia incision sites

- Laparoscopic approach – 3 to 5 cannula/port incision holes

Specimen Care #

- Resected tissue – peritoneal sac (sometimes called hernia sac) = excess slack peritoneum is resected after sac contents have been reduced to anatomical position

- Culture and sensitivity – swabs sent if mesh is infected in recurrent hernia repairs

Dressings and Drains #

- A strip dressing is sufficient for most procedures

- Steristrips and bandaids for laparoscopic port holes

Biliary System/ Pancreas/ Spleen Lecture #

Accessory Organs of Digestion #

The acessory organs of digestion include:

- Teeth and tongue: responsible for the mastication of food and mixing it with saliva to create a soft bolus that is swallowed into the esphagus

- Salivary glands: include the submandibular, parotid and sublingual. Produce buffers and lysozymes (to fight bacteria) and salivary amylase (mainly from the parotid gland) to aid in breaking down food in the stomach, prior to the introduction of gastric acid.

- Liver: works to detoxify and filter the blood, provide vitamin storage, and aids in fat absorption by producing bile

- Gallbladder: stores and secretes bile through the cystic duct and then into the common bile duct into the duodenum

- Pancreas: responsible for production of insulin and pancreatic enzymes to aid in protein digestion (secreted into the duodenum via the common bile duct)

- Vermiform appendix: discussed previously in GI lecture – no clear function in adult life

This lecture will cover the liver, gallbladder and the pancreas. The structures of the mouth (tongue and teeth) and the salivary glands will be discussed further in your ENT and Neck lectures (note: surgery of the teeth is usually done by an oral surgeon rather than an ENT surgeon).

The spleen is included in this section due to it’s proximity to the pancreas and because it does not really contribute itself to other system classification.

Liver #

Liver Anatomy and Function #

The liver is the largest gland in the body and weighs between 1.5-2 kilograms. It is situated under the diaphragm in the right upper abdominal quadrant (right hypochondrium). It is covered by peritoneum and a dense connective tissue layer beneath. It has two main lobes – the right lobe is separated from the smaller left lobe by the falciform ligament (which anchors the liver to the anterior abdominal wall and the diaphragm). Posteriorly, the liver has two more lobes – the caudate lobe, which is next to the inferior vena cava and the quadrate lobe, which the gallbladder lies next to. The ligamentum teres, extends from the falciform ligament down to the umbilicus.

Liver Blood Supply #

The liver blood supply is unique in the body. It receives a double suppy of blood – oxygenated blood from the systemic circulation via the hepatic artery and deoxygenated blood from the digestive organs – particularly the spleen, stomach, pancreas and intestines that is rich in absorbed substances – via the portal vein. This supply of deoxygenated blood is called the portal circulation. Both blood supplies mix together in the hepatic veins. Once the blood is filtered through the liver, it leaves via the inferior vena cava and circulates back to the heart. This arrangement has a large effect on patient’s with liver disease, especially liver cirrhosis, as the blood can back up as it has difficulty entering the liver – esophageal varices being one side effect.

Liver blood supplyPortal circulation

Liver Function #

The liver is responsible for:

- Oxygen, nutrient and toxin extraction from the blood by the hepatic cells

- Breaks down hemoglobin (uses metabolites of bilirubin in bile production) and hormones (one is insulin)

- Produces bile to aid in fat digestion – produces 600-1000cc of bile/day

- Synthesizes lipoproteins and cholesterol

- Produces albumin – osmolar component of blood serum

- Plays a role in blood clotting – production of clotting factors I (fibrinogen), II (prothrombin), V, VII, IX-XI. Also in produces hormones to regulate platelet production by the bone marrow.

- Storage of fat soluble vitamins – Vitamens A, D, E and K – and minerals

- Detoxification process – brings about metabolic alterations of foreign molecules or biotransformation of chemicals

- Regulator of blood glucose concentrations – breakdown of glycogen to glucose and other synthesis

- Red blood cell production in the fetus, until 32 weeks gestation where the bone marrow takes over

Pathology of the Liver #

Some pathologies of the liver are more common than others. The ones that require surgery are:

Hydatid Cysts

Hydatid cysts develop from amebic abcesses containing the larvae of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus. The “ingested” eggs are carried from the intestinal tract to the liver via the portal circulation. Patients are treated with medication (antibiotics) and excsion of the cysts. It is important to prevent spillage of the contents of the cysts to prevent the risk of anaphylaxis (due to high concentrations of contents into the circulation) and seeding of “daughter” cysts.

Removed large hydatid cysts

Liver Abcess

Abcesses are localized collections of pus caused by the spread of bacteria or other organisms via the portal circulation or a direct route from trauma, the biliary tract or via the hepatic artery; or by an extension of a preexisting abcess in the subdiaphragmatic or subhepatic area. The most common is from the biliary tract (i.e. empyema of the gallbladder or common duct stones). Abcesses can by solitary or appear in multiple sites within the liver.

Drained abcesses in a piece of resected liver

Tumors

Primary tumors of the liver are much more rare than secondary tumors, which usually arise as metastases from colorectal cancers. The tumors can be benign or malignant. The immediate treatment is surgical removal either through a wedge resection or lobectomy.

Cross section of a tumor within a lobe of liver

Trauma

Blunt trauma to the right upper abdomen can result in trauma to the liver, which can be treated nonsurgically if the patient is stable. Unstable patients, as well as patients with penetrating wounds to the liver, require surgery. The liver is highly vascular and can casue significant blood loss. Also, the integrity of the liver must be preserved. If the trauma is significant, the chest cavity may need to be entered as well (prepare the patient – skin prep and drape – as though this possiblity can occur). The liver may be lacerated and require suturing or require a wedge resection of the damaged tissue. The bleeding may be so diffuse, that the area may be packed with sponges to stop the bleeding with pressure.

Lacerated liver

Portal Hypertension

As mentioned previously, an increase in the venous pressure in the portal circulation (i.e. associated with cirrhosis of the liver), can cause compression or occlusion in the portal or hepatic system. This results in splenomegaly, large collateral veins and ascites; and in severe cases systemic hypertension and esophageal varices. The surgical treatment is portocaval (venous) shunting (i.e. LeVeen shunt) to bypass some of the venous blood from the damaged liver. Ruptured esophageal varices in themselves are an emergency situation.

View down a gastroscope at enlarged esophageal varices

Surgery of the Liver #

Incision and Drainage

Liver abcesses require a laparotomy and open drainage of the abcess. Cultures, both anerobic and aerobic, are taken. The area is flushed with copious amounts of irrigation to flush out all pus and debris.

Hytadid cysts are removed in their entirety, with care taken not to ruture them. The area is again flushed with irrigation. If the cyst is ruptured, the area is flushed extensively.

Repair of Liver Laceration

As mentioned above, trauma to the liver is about contolling bleeding of the liver and liver bed. The laceration or tears in the liver are sutured with a PDS or similar suture – a blunt needle may be used to stop further cutting damage to the liver. Packs are removed individually and slowly, so as to not reinitiate bleeding. Once the initial bleeding has subsided and the surgeon is able to gain visibility, hemostasis is maintained. This may be done with an Argon Beam Coagulator – a special cautery that uses argon gas to propel electricity out of the tip of the cautery pencil in a spray-like fashion. This spraying allows for a wide area of diffuse bleeding/ oozing to be controlled. Go to the following link to read more about Argon Beam Coagulation. The Argon Beamer, as it is often called, and hemostatic agents are also used in other surgeries of the liver, due to its vascularity. Other types of hemostatic agents include: Gelfoam, Avitene, Surgicel and Tisseel. All of these are fibrin stimulating type agents used to seal off or clot blood vessels.

Not all centers are capable of dealing with liver trauma. At times the source of bleeding is unknown a laparotomy will be performed. Once it is known that it is due to liver damage, the liver will be packed with sponges, the patient is closed and then sent to a center that is able to deal with high acuity patients. Ensure that all sponges packed and retained within the patient are documented (and the documentation is sent with the patient), so that the receiving center will know what will need to be removed. The receiving center must document how many sponges were removed. Drains are usually inserted to monitor drainage.

Tumor Resection

Enucleation: Removal of benign tumors that are noninvasive. The encapsulated tumor is resected and bleeding is controlled. Depending on the location of the liver a more extensive resection may need to be done. Some tumors are able to be removed with a machine called a CUSA (Cavitron Ultrasonic Aspirator). This special machine breaks up tumor with ultrasonic waves that cut and emulsifiy tissue, while at the same time diluting it with fluid irrigation, so that it can be suctioned it away.

CUSA handpiece and machine