Description #

This unit will review the potential adverse reactions and complication of neuronal blockade with a brief discussion of management and prevention.

Learning Objectives #

Learning Objectives:

- Understand the adverse reactions and complications of peripheral nerve blocks.

- Understand the management of the complications of peripheral nerve blocks.

- Understand and consider prevention strategies to avoid peripheral nerve block complications.

#

Introduction: #

Local anesthetics should be administered in the appropriate dosage and in the correct anatomical location to enhance safety. A one-year prospective study by the French-Language Society of Pediatric Anesthesiologists included 24,409 regional anesthesia procedures in children. The study documented only 23 minor complications all of which occurred after neuraxial blocks. This study showed that peripheral nerve blocks (PNB) are safe compared to neuraxial blockade [1]. However, systemic and localized toxic reactions can occur, usually as a result of accidental intravascular/intraneuronal injection or administration of an excessive dose.

Contraindications: #

Absolute contraindications to PNBs include:

- Infection at the puncture site and sepsis;

- Bleeding disorders or anticoagulant therapy;

- Allergy to local anesthetics (rare); and

- Parent/Patient refusal .

Complications of PNB’s can be divided into two categories: #

#

#

Drug Related Complications: #

CNS Toxicity:

Local anesthetics are lipophilic, weak bases that easily cross the blood-brain barrier. Animal models have shown that hypercapnia or acidosis increases the risk of CNS toxicity from local anesthetics . In general, because the CNS is more susceptible than the CVS to the actions of local anesthetics, CNS symptoms normally precede CVS symptoms.

Notes: 1) The maximum dose for bupivacaine is 2.5 mg/kg. The maximum dose for Lidocaine is 7 mg/kg with epinephrine and 3 mg/kg without epinephrine.

2) Aminoamides (such as lidocaine and bupivacaine) are metabolized primarily by hepatic cytochrome P450-linked enzymes.

3) Systemic toxicity (neurologic and cardiac) is increased in patients with right-left cardiac shunts.

Progressive Symptoms and Signs of CNS Toxicity: #

Management: Routine Seizure and CNS depression management.

Direct Cardiac Effects of Local Anesthetics: #

Local anesthetics primarily act on the sodium channels leading to a decrease in the rate of depolarization . Extremely high concentrations of local anesthetics depress pacemaker activity in the sinus node, resulting in sinus bradycardia and sinus arrest.

All local anesthetics exert a dose-dependent negative inotropic action on cardiac muscle proportionate to their potency. In addition, bupivacaine binds irreversibly to cardiac muscle. Thus, bupivacaine is a more potent cardiodepressant than lidocaine.

Ventricular arrhythmias may occur after rapid intravenous administration of a large dose of bupivacaine but far less frequently with lidocaine .

Direct Peripheral Vascular Effects: #

At low concentrations, lidocaine and bupivacaine produce vasoconstriction, whereas high concentrations cause vasodilation. Local anesthetics also increase pulmonary vascular resistance, but this response may reflect circulatory or respiratory depression from the drugs’ effects on the CNS.

Management: In addition to routine management of cardiac arrest, studies suggest that a bolus of 20% Intralipid followed by infusion until the patient is stable may improve outcome by extracting the lipid soluble bupivacaine molecules from the aqueous plasma phase.

Allergies: #

Note: Local anesthetics are available in a preservative-free preparation.

Needle Related Complications: #

Four Mechanisms of Nerve Injury

1) Intraneural injection:

High intraneural pressure can exceed capillary occlusion pressure leading to nerve ischemia . Mechanical destruction may result in inflammation, cellular infiltration and axonal degeneration, which can lead to nerve scarring and chronic neuropathic pain. The current evidence suggests, however, that neurologic injury does not always develop after an intraneural injection.

The major concern with injecting local anesthetic near a nerve is accidental injection under pressure into the perineurium causing long-term permanent nerve injury.

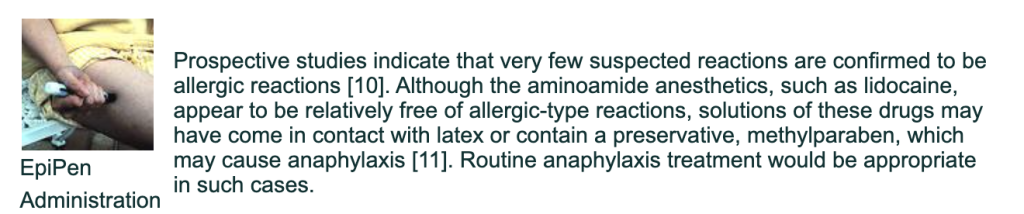

Figure 1: A peripheral nerve (made up of fascicles) surrounded by perineurium, epineurium and nourishing blood vessels

Note: The larger the nerve, the greater the risk of intraneural injection.

2) Mechanical: #

Laceration – The nerve may be cut partially or completely by the needle causing paresthesia and loss of function.

Stretch – Nerves or plexuses can be stretched in a nonphysiologic or exaggerated physiologic position leading to injury.

3) Vascular: #

Hemorrhage within the nerve secondary to vessel puncture from the needle.

Ischemia secondary to acute occlusion of the arteries may lead to tissue destruction. Nerve function generally returns within 6 hours if ischemia lasts for under 2 hours. Ischemic periods over 6 hours risk permanent structural changes to nerves.

4) Chemical: #

Drug injected directly into the nerve or into adjacent tissues, may cause an acute inflammatory reaction or chronic fibrosis. The toxicity and ultimate damage to nerve tissue is related to the site of action, time of exposure and the type and concentration of local anesthetic agent used . Intraneural concentrations are generally below the threshold for toxicity because the solutions spread through tissues and diffuse from the injection site into the nerve.

Management of Nerve Injury: #

Most symptoms of nerve injury resolve in four to six weeks in over 95% of patients, and in 99% of the patients by one year [18]. Following PNB, if sensory and/or motor function remains depressed beyond the expected duration, potential causes should be investigated. Neurologic deficits may also be related to improper positioning, post-manipulation swelling, and/or pre-existing neurologic deficits.

Should neurologic injury be suspected, all patients should be referred to neurology who will consider further investigations such as electrophysiology, high-resolution ultrasound, and/or magnetic resonance imaging. Often PNB injury associated with neuropathic pain may need the involvement of the chronic pain team.

Prevention and Precautions: #

The following recommendations are suggested to decrease the risk of complications with PNBs:

Resuscitation Equipment and Medications:

The potential for respiratory depression, seizures and even cardiac arrest necessitates full monitoring. Resuscitation equipment, medications, anticonvulsants and 20% intralipid should be immediately available.

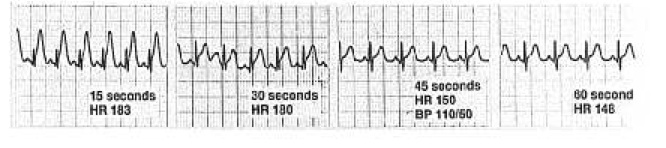

Note: Attention to the ECG may be the difference between a toxic and lethal dose.

Figure 2: Profound ST elevation and increased T-wave amplitude 15 seconds after an intravascular injection with bupivacaine with epinephrine followed by decreased heart rate and rapid resolution of ST-T changes after stopping the injection .

Fractionated, slow injections: #

Inject smaller doses and volumes of local anesthetics with intermittent aspiration to avoid inadvertent intravascular injection and to decrease the risk of channeling of local anesthetic to the unwanted tissue layers, lymphatic vessels, or small veins. This approach permits detection of local anesthetic toxicity before the entire dose is injected.

Note: If the needle is in a small vessel, aspiration of blood is not always present.

Avoidance of injection against abnormal resistance: #

Intraneuronal needle placement may result in high resistance to injection due to the compact nature of the neuronal tissue and its connective tissue sheaths. Always use the same large syringe (20ml) and needle size to develop a “feel” during the injection [13]. When injection of the first milliliter of local anesthetic proves difficult, the needle should be slightly withdrawn and the injection attempted again. If resistance persists, the needle should be completely withdrawn and flushed before repeating the insertion.

Caution: Manual assessment of the resistance to injection using a hand-feel method is highly subjective and depends on the speed of injection, needle size, and operator expertise.

Abort injection if pain is reported by the patient: #

Severe pain or discomfort on injection may signify intraneural placement of the needle. The injection must be stopped if pain is elicited.

Caution: No pain does not indicate lack of intraneural injection . Lancinating, “shooting” pain on injection should not be confused with a mild normal “paresthesia-like” report by the patient when the needle is placed in the immediate vicinity of the nerve. In practice it can be difficult to discern when pain-paresthesia on injection is “normal” and when it is a sign of an intraneural injection.

A few more tips: #

Choose your local anesthetic solution wisely. Always choose a shorter acting local anesthetic when long-lasting analgesia is not required.

Repeating blocks after a failed block. Repeating a block after a failed attempt is not recommended as the patient may no longer be able to reliably assess pain.

Aseptic technique. Most nerve block techniques are merely percutaneous injections. However, infections are known to occur and this almost entirely preventable complication can result in significant disability.

Needle choice. The evidence for the type of needle used is not currently helpful for everyday clinical practice. Wherever possible dedicated nerve block needles should be used

Surface localization. Surface localization with ultrasound of superficially seated nerves can help reduce the number of needle passes and the volume of local anesthetic required for successful blockade.

Post-block care. Patients discharged with prolonged block need advice regarding preventing trauma to anesthetized dermatomes.

References: #

- Giaufré E: Risks and complications of regional anaesthesia in children. Baillieres Clin Anaesthesiol 2000; 14:659.

- Dalens B, Mansoor O: Safe selection and performance of regional anaesthetic techniques in children. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 1994; 7:257.

- Englesson S: The influence of acid-base changes on central nervous system toxicity of local anaesthetic agents. I. An experimental study in cats. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1974; 18:79-87.

- Mazoit JX, Dalens BJ: Pharmacokinetics of local anaesthetics in infants and children. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003 (in press).

- Rosen MA, Thigpen JW, Shnider SM, et al: Bupivacaine-induced cardiotoxicity in hypoxic and acidotic sheep. Anesth Analg 1985; 64:1089-1096.

- Wagman IH, De Jong RH, Prince DA: Effects of lidocaine on the central nervous system. Anesthesiology 1967; 28:155-172.

- Lynch 3rd C: Depression of myocardial contractility in vitro by bupivacaine, etidocaine, and lidocaine. Anesth Analg 1986; 65:551-559.

- Kotelko DM, Shnider SM, Dailey PA, et al: Bupivacaine-induced cardiac arrhythmias in sheep. Anesthesiology 1984; 60:10-18.

- Weinberg GL: Current concepts in resuscitation of patients with local anesthetic cardiac toxicity. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2002; 27:568.

- Baluga JC, Casamayou R, Carozzi E, et al: Allergy to local anaesthetics in dentistry. Myth or reality?. Allergol Immunopathol 2002; 30:14-19.

- Shojaei AR, Haas DA: Local anesthetic cartridges and latex allergy: A literature review. J Can Dent Assoc

- Auroy Y, Benhamou D, Bargues L: Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: The SOS regional anesthesia hotline service. 2002; Anesthesiology: 1274-80.

- Selander D: Peripheral nerve injury after regional anesthesia, Complications of Regional Anesthesia. Edited by Finucane B. Philadelphia, Churchill Livingstone, 1999, pp 105-15.

- Sunderland S: The sciatic nerve and its tibial and common peroneal divisions: anatomical and physiological features, Nerves and nerve injuries, 2nd Edition. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone, 1978, pp 925-991

- Klein S, D’Ercole F, Greengrass R, Warner D: Enoxaparin associated with psoas hematoma and lumbar plexopathy after lumbar plexus block. Anesthesiology 1997; 87: 1576-1579

- Gentili F, Hudson A, Hunter D: Clinical and experimental aspects of injection injuries of peripheral nerves. Can J Neurol Sci 1980; 7: 143-151

- Bainton CR, Strichartz GR: Concentration dependence of lidocaine-induced irreversible conduction loss in frog nerve. Anesthesiology 1994; 81:657-667

- Urmey W, Stanton J: Inability to consistently elicit a motor reponse following sensory parethesia during interscalene block administration. Anesthesiology 2002; 96: 552-4

- Freid,E B M.D; Bailey, A G M.D; Valley, R D M.D: Electrocardiographic and Hemodynamic Changes Associated with the Unintentional Intervascular Injection of Bupivacaine with Epinephrine in Infants, Anesthesiology 1993; 79: 394-398.

- Claudio RE, Hadzic A, Shih H, Vloka JD, Castro J, Koscielniak-Nielsen Z, Thys DM, Santos AC: Injection pressures by anesthesiologists during simulated peripheral nerve block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2004; 29: 201-5

- Bhananker S, Domino K: What actions can be used to prevent peripheral nerve injury. In Evidence-Based Practice of Anesthesiology. Edited by LA F. Philadelphia, Elsevier Inc, 2004, pp 228-235

- Miller: Miller’s Anesthesia, 6th ed. – 2005 – Churchill Livingstone, An Imprint of Elsevier

- New York School of Regional Anesthesia Website. www.nysora.com

- Google images

- Dr. Weinberg, Bupivacaine Toxicity in a Rat Rescued by Lipid emulsion video clip.